The Collision

In 1872, a report of a spectral visitation brought international attention to a rural spot in Minnesota. The place was called Randall Station at the time, but it’s now known as Clontarf. The ghost was recognized to be a railroad worker named Connelly, who had died in a wreck a few months earlier. What was his reason for lingering the physical realm? Apparently, Connelly was a devoted employee and not at all happy with having been replaced.

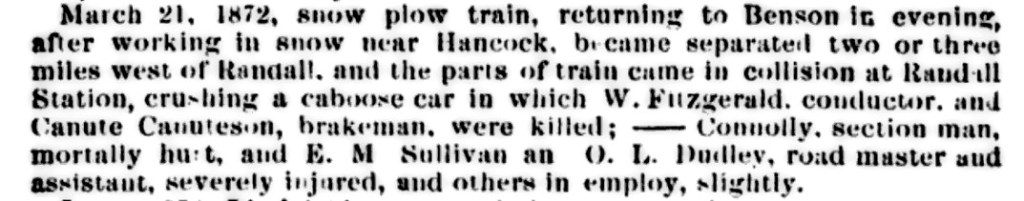

While an article on the March 21 train wreck on the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad — cited as the accident that killed Connelly — doesn’t mention a victim by that name, a subsequent and more officious report does. The two sources give a good account of how a multi-engine train was being used to plow snow along the tracks. One of those engines became detached, but the flying snow prevented the workers from noticing. That separated engine then slammed into the rest of the train after it had stopped at Randall Station.

In October, an article in the St. Paul Pioneer points to the disaster while explaining the appearance of Connelly’s vengeful ghost. Though I haven’t found that original report, Minneapolis’s Star Tribune reprinted it, introducing the piece as coming from a trustworthy paper. In the days that followed, the story was picked up by papers in several other states, including The New York Times. It even spread as far England and Scotland. Indeed, news of Connelly’s ghost traveled beyond the reach of the railroad.

Connelly Is Replaced — with Connelly

The Pioneer article portrays Connelly as having been an exemplary employee. He was “very much attached to his division” and kept “everything right and tidy” there, despite it being on a bleak and blustery prairie. After he was killed, the position was filled by a man bearing the very same surname. This second Connelly is described as “sober, industrious, and intelligent,” not a man one would “suspect of being tinctured in the slightest degree with superstitious notions.” Still, being replaced is one thing. Being replaced by someone with the same name is another. The first Connelly — whose only shortcoming was having died — would let his vexation be known!

The ghostly Connelly — let’s call him “Connelly A” for apparition — used various means to express his disdain for the new guy. Let’s call this poor fellow “Connelly B” for breathing. Connelly A visited Connelly B’s bedside, where he “vainly endeavors to tell his tale by unearthly motions, at times apparently entreating, and anon with every appearance of anger and revenge.” The spiteful specter managed to yank the living man out of bed, leaving “the marks of rough handling,” including prints made by hands and fingernails. Connelly A even plagued Connelly B during the day.

There were other witnesses, too. In fact, Connelly B kept quiet about what he was experiencing until other workers saw the figure. They were eating supper when the phantom materialized and “remained long enough to make a number of demonstrations of a revengeful character….” Though the apparition vanished, the horrified men had recognized their former colleague. Only then did Connelly B share what he had suffered, and it was probably shortly thereafter that his experience went viral 1872-style.

The Pioneer Defends What the Star Tribune Debunks

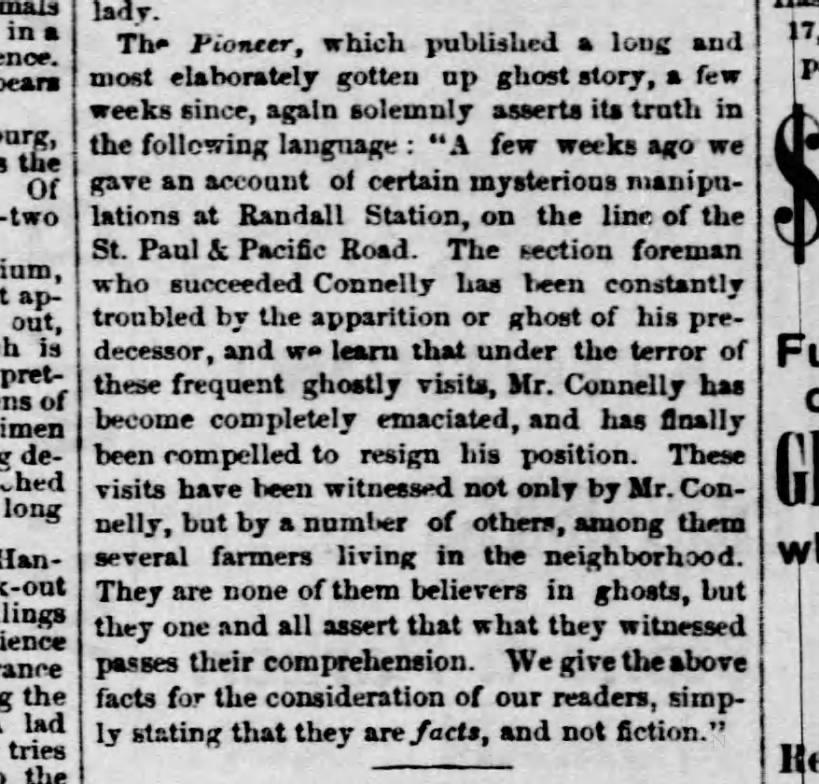

Given the widespread attention the weird story was getting, it’s probably not surprising that the reliability of the Pioneer was called into question. They defended the original article, however, restating its key points and then affirming that “they are facts, and not fiction.”

Nonetheless, the Star Tribune launched its own investigation and published the findings in January, 1873. The unnamed reporter opens by giving a thorough recap of the story, silently correcting the paper’s March report of the collision by adding Connelly’s name and changing another. Here, readers learn that the two Connelly men were brothers, and both were involved in the wreck. The surviving brother “was injured in the spine to such an extent that his mind was probably somewhat affected,” according to this follow-up story. The reporter then casts further aspersions on Connelly B by pointing out that he immigrated from a country “where the poorer classes at least believe in ghosts and goblins.” Given the surname, readers are asked to accept a far-from-flattering stereotype about the Irish here.

The reporter goes on to dismiss the other witnesses as the gullible prey of two engineers pulling a prank. Exactly how this was uncovered isn’t explained. The skeptical scribe next points out that, since the ghost report was first published, several curious visitors to the station house had failed to witness any ghost. However, two of them succeeded! And yet the reporter discounts those two as “evidently disposed to keep up the joke,” again with no explanation of how this was revealed. The piece ends with the implication that Connelly — earlier dubbed mentally impaired and ethnically superstitious — is attempting to cleverly dupe the railroad company into building him a new house away from the haunted spot. As far as disproving supernatural phenomena goes, this attempt to debunk is pretty easy to debunk.

Finding Where the Station House Was

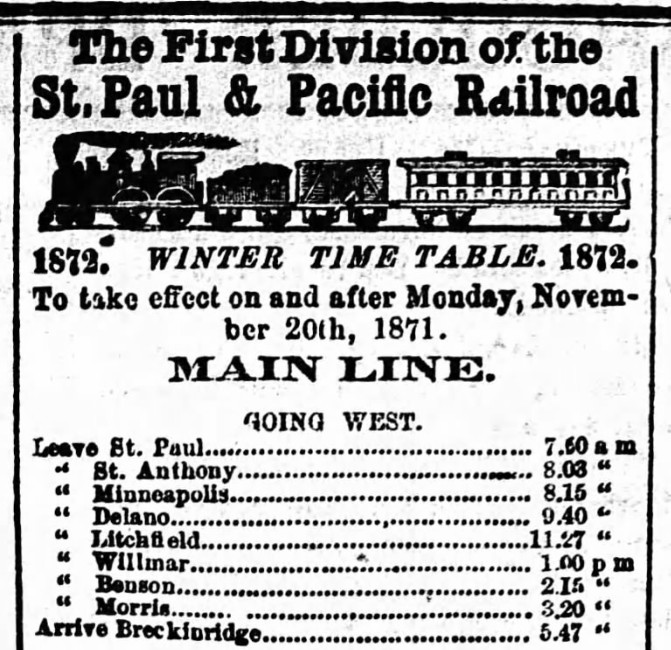

In 1877, the area near Randall Station became a settlement called Clontarf, and this name remains. Presumably, the old tracks were where the current ones are, since they still connect Benson and Morris. This map shows they run parallel to Route 9, a bit to the west. I haven’t been able to determine exactly where the station house stood, but the phenomena weren’t confined to this structure. The Pioneer article says the ghost hid the trainmen’s tools, which very likely were stored near but outside the station house itself. In addition, an engineer is cited as having seen “the apparition in the night at work upon the track.” At times, it gave warning signals to the engineer and somehow slowed down the locomotive — as if it were plowing through deep snow — until it reached a certain distance beyond. Given this radius of activity, a ghost hunter might have luck investigating more than just where the house had been.

I usually like to end these “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” posts with other nearby attractions related to ghost hunting or railroad history in case the old ghost has retired. Unfortunately, Clontarf is a hamlet whose population ranges between 150 and 200. It has an interesting history, one intertwined with the heyday of railroading, but there’s not much there today. Let me suggest, then, you make it part of a road trip that combines Anoka, Halloween Capital of the World, with some of the haunted sites in the Twin Cities. And if you visit any of these places, please let us know about it in the comments below.