Ghosts Tied to Time

There’s something weirdly appealing about the idea of an “anniversary ghost.” This is a spirit who, though having moved on to another dimension, returns to the physical realm on a strict schedule. Henry Holt Moore, writing in 1891, contrasted such old-fashioned ghosts to the new, nineteenth-century kind, which “come at no yearly anniversary….” However, in her 1919 memoir, Ghosts I Have Seen and Other Psychic Experiences, Violet Tweedale relates her neighbor’s “very tantalizing experience” with an anniversary ghost, saying the encounter happened “a very few years ago….” The neighbor saw the apparition and became enchanted by it! He noted the date and, to be sure, witnessed it again exactly one year later. Such annual manifestations have many precedents, and if I lived in a haunted house, I’d prefer such a spectral housemate — I could either make popcorn and await its performance or, if that proved too unsettling, make plans to be elsewhere that night.

All of this helps to explain why, in 1873, a large crowd gathered in Newark, New Jersey, to witness a phantom locomotive said to manifest with the regularity one might expect from a more tangible train. It was reputed to leave Broad Street Station on the 10th of every month. Let me begin at the beginning, though.

A Wreck on a Wet, Autumn Night

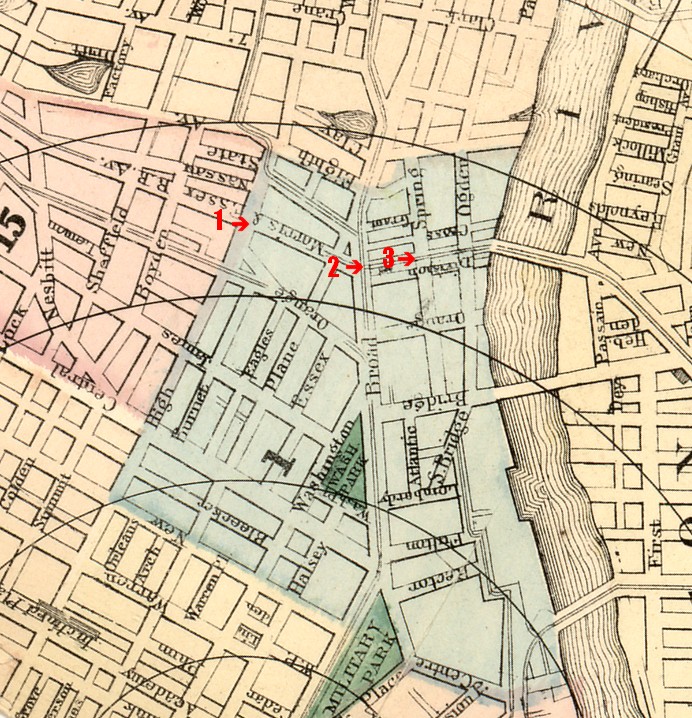

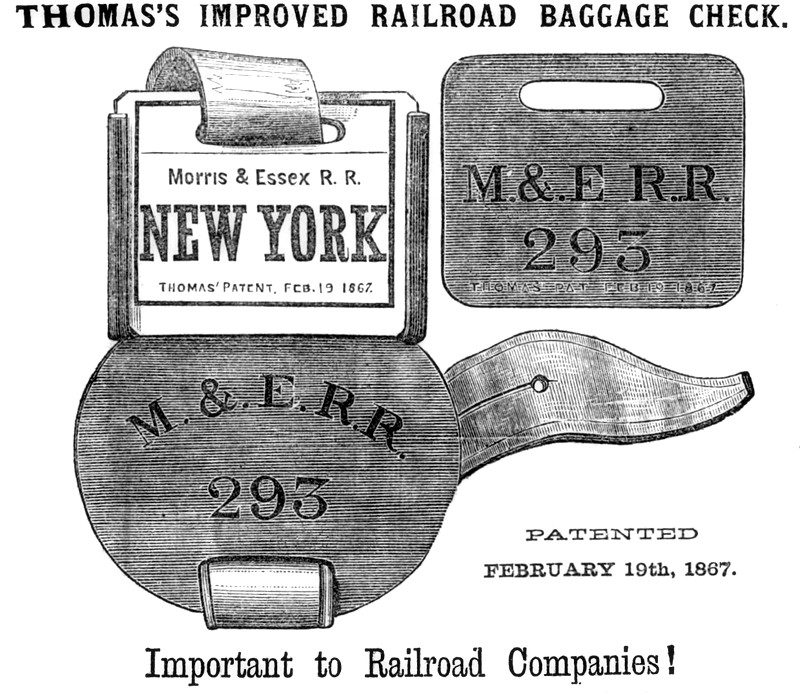

On September 26, 1868, a train tragedy occurred in Newark, which the New York Herald described the next day as a “collision of a serious character.” On the 28th, a fuller account appeared in the Elizabeth Daily Monitor, and here we learn that the collision involved a train belonging to the Morris & Essex Railroad (M&E). The engine, hauling 36 cars of coal, “was brought to a standstill at High street, on the heavy down grade of the road, about one-eighth of a mile from the depot….” (See 1 on the map below.) Battling gravity and wet tracks, engineer Nathan Nichols was unable to keep the train from slipping downhill, and it resumed its course “with fearful velocity.” The fireman, brakeman, and conductor each managed to leap off before the engine collided with another train sitting at Park Street. (See 2.) With Nichols still at his post, the coal train derailed. It continued on, sideswiping “a dwelling house, occupied by a family named Conkling, on the northeast corner of Spring and Division streets.” (See 3.) This was enough to bring the runaway locomotive to a terrible halt.

Miraculously, the Conklings survived. However, when the rubble was cleared, Nichols was found dead. His funeral was held at the Eighth Avenue ME Church, being presided over by the Reverend Charles E. Little, and the trainman was buried in Evergreen Cemetery. Oddly, later that same night, Michael Burns, a M&E flagman at the Broad Street crossing, was run over while attempting to shepherd pedestrians away from another passing coal train. He died, too. A later report says he was considered “a victim to his own carelessness,” which strikes me a harshly worded when considering his kind effort.

A Phantom Locomotive Reported

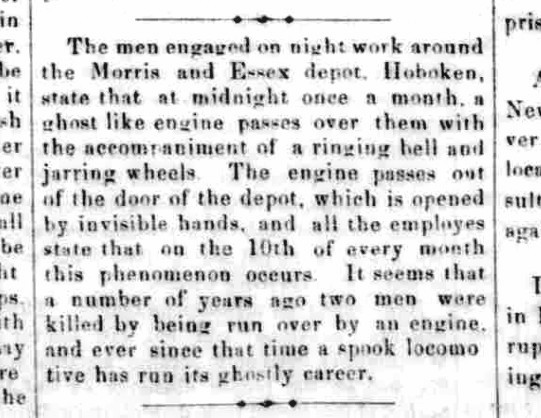

Five years later, a phantom locomotive was reported to appear at the Broad Street Station. It was tied to that night of death and narrow escapes. For some reason — maybe simply the passage of time — the earliest report I’ve found links the manifestation to Hoboken, where Nichols was headed, instead of to Newark, where he died.

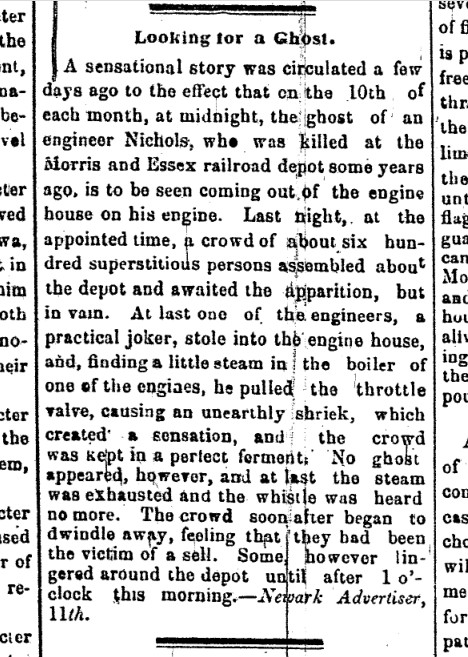

Subsequent reports confirm that the phantom train was witnessed in Newark, though, and the figure of Nichols was observed sitting in the engineer’s seat. Here’s an article published a couple of days later:

From there, the news traveled to places such as Maine, Virginia, Ohio, and Tennessee. All of the newspapers in these states attribute Newark’s Courier as their source, saying that the wreck that led to Nichols’ death had occurred on October 10th. This is incorrect, of course, but without the remarkably handy technology of online archives, who would know? Admittedly, this mistake, the failure of the spectral locomotive to appear, and the “practical joker” mentioned above combine to give this case the fragrance of a hoax or, at the very least, of a tall tale.

Is It Still Worth Investigating?

Despite the reasons to doubt the story, the specificity of the backstory — the fact that the apparition can be traced to an actual wreck with verifiable fatalities — adds a pinch of credibility. Besides, who isn’t a sucker for a phantom locomotive? The site is conveniently located, too, and Division Street, where the runaway train finally halted, is walkable. Therefore, I say it’s worth some spook-snooping.

The building around which all those hopeful but disappointed ghost-seers had gathered in 1873 was eventually demolished, and the present Broad Street Station was put in its place in 1901-1903. Nonetheless, this new structure is rich in history, making it worth a visit for train enthusiasts. For those more interested in the paranormal, Newark has more than just the Jersey Devil to make it interesting, from a witch named Moll DeGrow to a ghost named Annie Crest. It’s also the home of Henry William Herbert (1807-1858), a founding writer of occult detective fiction. In a spooky twist, the very same year that engineer Nichols’ ghost was reputed to have returned, author Herbert’s ghost made news, too!

As always, if you conduct even a casual ghost hunt in the area of Park Street Station, please share your findings below.