Confirming Crowe’s Authorship

Though a short story titled “Loaded Dice” was published anonymously in an 1850 issue of Household Words, two sources confirm that it was written by Catherine Crowe. One is the office book of the journal’s subeditor William Henry Wills, which is transcribed in Anne Lophrli’s index Household Words: A Weekly Journal 1850-1859 Conducted by Charles Dickens (U of Toronto Press, 1973. The entire index is available online in the U.S. at Hathitrust, and those elsewhere can see the story’s entry at Google Books.)

The other source is more illuminating. Charles Dickens, editor of Household Words, wrote to Wills regarding Crowe’s story a couple of months before it was printed. Apparently, the famous author wasn’t too keen on “Loaded Dice,” which begs the question of why he published it. He says:

Mrs. Crowe's story I have read. It is horribly dismal; but with an alteration in that part about the sister's madness (which must not on any account remain) I should not be afraid of it. I could alter it myself in ten minutes.

It might be easy to agree with Dickens, since “Loaded Dice” is probably not one of Crowe’s better short works. One weakness might be seen in the story’s narrative frame. This tale repeats a pattern that Crowe uses in an earlier crime story, “An Adventure in Terni” (1841): two travelers, one acting as narrator, come upon something mysterious and — after conducting some subsequent, “offstage” inquiry — the narrator relates the backstory that accounts for the mysterious something. Crowe is following the basic format of a mystery story. But with Step 2 missing.

Step 1) Client walks into the detective’s office with a mystery,

Step 2) detective investigates, and

Step 3) the backstory is unveiled.

Of course, I’ve oversimplified things here, but I think you see my point. If Crowe had spent more time with that middle chunk, she might be better remembered as an important figure in the history of the mystery. At least, we would see why the visiting narrator plays an important part in the tale. On the surface, it seems like this story could’ve been told without the framing device.

Dying of Shame

Another weakness might be in the fact that, while “An Adventure in Terni” involves a murder, “Loaded Dice” is about a young man cheating at gambling. The stakes are much lower here, and — as Dickens implies — Crowe leans pretty hard on how Charles Lovell’s surrender to temptation led to melodramatically dire consequences, including a character literally dying of shame. A soldier named Herbert is engaged to Charles’s sister, Emily, and he loses all of his savings to Charles’s cheating. Crowe writes:

[Herbert] determined instantly to pay the debts, but he knew that his own prospects were ruined for life; he wrote to the agents to send him the money and withdraw his name from the list of purchasers. But how was he to support his mother's grief? How meet the eye of the girl he loved? . . . The anguish of mind he suffered then threw him into a fever, and he lay for several days betwixt life and death, and happily unconscious of his misery.

If that isn’t enough suffering, Herbert recovers — and, the day after he learns Charles has been accused of cheating, the soldier “was found a corpse, and a discharged pistol lying beside him.” If that isn’t enough suffering, Emily hears about her brother’s cheating and her fiancé’s suicide, and wouldn’t ya know it:

Before Herbert's funeral took place, Emily Lovell was lying betwixt life and death in a brain fever.

This seems to be where Dickens stepped in and quite possibly saved Emily’s life or, at least, reduced her pain with a red pencil. In the end, she accompanies Charles in self-imposed exile in Australia. This, one presumes, is preferable to death, if only for the nice beaches down under.

A Lesson about the Dangers of Gambling — or A Lesson about the Dangers of Poverty?

It would be easy to see “Loaded Dice” as a didactic, if not downright preachy, tale about the dangers of gambling. That, after all, is the root of all the high tragedy here. However, the title might be more significant than just one of the ways Charles was found cheating. (He also manipulates the cards to his own advantage.) Were the metaphorical dice, the Dice of Fate, loaded to the disadvantage of Charles, a good guy who happened to be born into poverty?

Crowe spends a good amount of time establishing that Charles is the product of a good family, and here’s where the two travelers/narrative frame does play an important role. The travelers discuss how the cheater’s father is the local vicar, who married for love rather than for money and who was promptly disinherited by a rich uncle as a consequence. Though poor, Charles was raised in an idyllic, rural environment. The narrator’s companion even says that “poverty might be poetical and graceful here.” This is not at all the filthy streets and grimy workhouses of London, where Dickens’ Oliver Twist grew up. In fact, one might argue that what Dickens had done to link crime to urban poverty in that 1838 novel is being done here for the rural equivalent. Financial desperation very much explains Charles’s succumbing to cheating, illustrating how criminals are made, not born. (That this debate was on people’s minds is suggested by Cesare Lombroso formally articulating the “born criminal” theory in 1876. An English translation is here.) Thinking of Crowe’s short story in these terms helps to make it a more sophisticated piece than the “horribly dismal” one that Dickens deemed it.

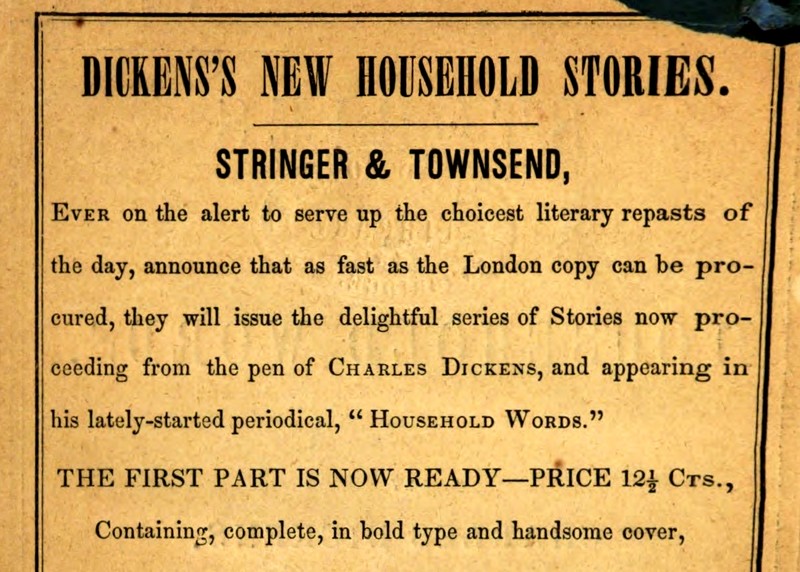

A Couple of (Probably Pirated) Reprints

And this might explain why not everyone agreed that “Loaded Dice” is as overwrought as Dickens did. A New York publisher reprinted it in Stories from Household Worlds (1850), a series promoted as offering “the choicest literary repasts of the day.” In a similar anthology from another New York published, one titled Pearl Fishing: Choice Stories from Dickens’ Household Words (1854), the editor introduces the contents as “judicious selections” from Dickens’ journal, “embracing some of its best stories.” Well, if nothing else, “Loaded Dice” was being sold as quality stuff.

However, Crowe still goes unnamed in both of those anthologies, and the words “by Charles Dickens” on the title page of the earlier one along with “from the pen of Charles Dickens” in its promotional copy can easily mislead a reader into thinking he’s the author. Transatlantic copyright protections were a mess at this time, and it’s entirely likely Crowe received neither a cent nor a pence from the New York publishers. The same can be said when the story reappeared in Recollections of a Policeman (1856), published in Boston, Massachusetts. Here, the author is blatantly named as “Thomas Waters, an inspector of the London Detective Corps.” Oh, the irony: falsely attributing a pirated tale to a police officer. Nonetheless, this shows that Crowe’s work was being understood as a piece of crime fiction.

A couple of decades later, another victim of pirating — an author known as Mark Twain — would campaign for better domestic and international copyright protection. As for Catherine Crowe, her crime story would be stolen away. The Dice of Fate were loaded to her disadvantage.