A criticism of modern detective fiction would obviously be inadequate without some appreciation of the great Sherlock Holmes cycle…. A man who had not heard of Holmes would be more singular than a man who could not sign his own name.

— Cecil Chesterton, “Art and the Detective” (1906)

You’re a Wizard, Sherlock

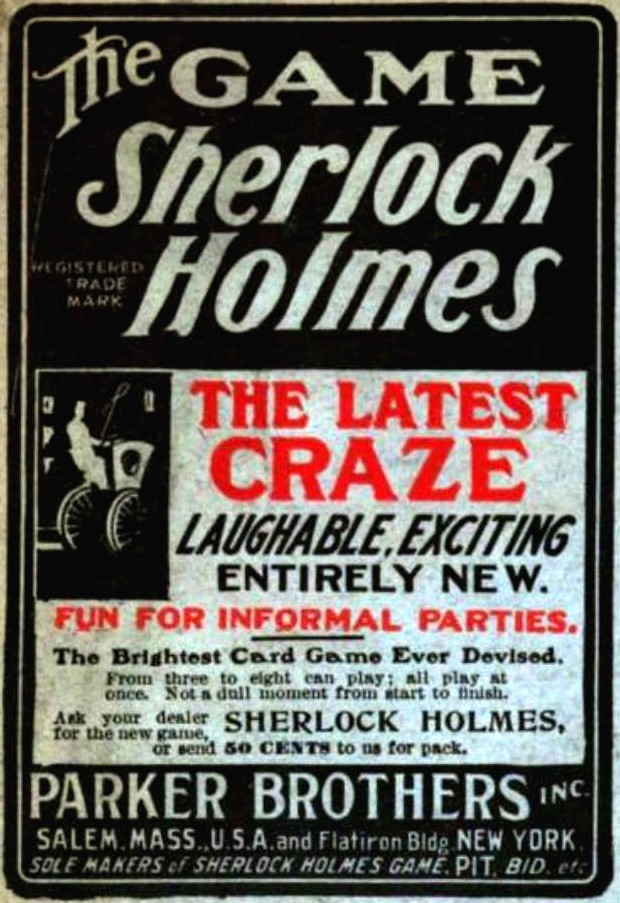

Do you remember the level of popularity that Harry Potter generated as the 20th century became the 21st? I imagine this is the closest equivalent we have to the Sherlock Holmes craze of a century earlier. I keep bumping into references to Holmes whether I’m looking at critics’ responses to that era’s criminal characters for the Curated Crime Collection or reading tales for the Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives. The Bodacious Brain of Baker Street even pops up in at least one survey of haunted sites. As Cecil Chesterton notes in the 1906 essay quoted above, Sherlock Holmes had become a part of everyday language in a way that very few other fictional characters can claim.

Close upon the heels of Arthur Conan Doyle’s newfound fame, mystery fiction swelled with competitors, a swarm of scribes who brought a diversity of detectives often appearing in short-story series. In The Golden Era of Sherlock Holmes and His Contemporaries (Genius, 2024), Michael Cohen explains that his “concentration is on those features that led to Conan Doyle’s success and how those following him employed and transformed them.” Cohen proves himself to be very well-read in this wave of mystery fiction, introducing readers to a library full of potential new reading material in chapters devoted to imitations/sharp revisions of Holmes, to women detectives, and to medical and other scientific crime-solvers. I was especially happy to see a chapter devoted to the kind of criminals whose exploits I curate — and another to those investigators whose dealings with ghostly clients and demonic culprits qualify them for my bibliography.

The Pluses and Problems of Parameters

Cohen sets the parameters for his material pretty firmly between 1891, when the first Holmes short story debuted, and 1918, when World War I ended. To be sure, along with a lot of conventional detective fiction, these years also encompass a wide range of innovative, even experimental, work. As the author says:

The genre-extending and changing, the deconstruction, the repeated failures, the intertextuality, reflexivity, and metafiction characteristics of this First Golden Era of detective fiction are worth pointing out and naming.

As we wander through the many authors and characters, Cohen adds dashes and splashes of connections to Holmes, references to Edgar Allan Poe, historical contextualization, and his personal preferences. I especially appreciated his explanation of how changing trends in publishing herded detective fiction away from novels and toward short-story series — and, afterward, back to novels.

However, a book of this type necessitates a great deal of plot summary (and Cohen divulges a good many endings, too). In this regard, I found reading the book straight through a bit sluggish, but perhaps Golden Era is better understood as a reference work that can be read bit by bit, now and again, to discover new reading material. And Cohen provides a long list of online sources for the works he discusses in case readers have come upon a character or two who have sparked their interest. I was honored to see my Chronological Bibliography included there.

Nonetheless, the time frame might also help explain why Cohen falls back on a truncated history of occult detective fiction that scholars digging deeper have extended to many decades earlier. Cohen opens his chapter titled “Occult Detectives” by bluntly stating:

The occult or psychic detective in fiction is a late nineteenth century invention, though some have made an argument for Sheridan Le Fanu's Dr. Hesselius, a minor character in one of his books that collects earlier stories, In a Glass Darkly (1872).

In keeping with some literary historians (two of whom I discuss in Part 3 of “Settling on a Definition of Occult Detective Fiction”), Cohen names John Bell, L.T. Meade and Robert Eustace’s debunking detective, and Flaxman Low, E. and H. Heron’s expert on genuine spooks, as the first characters to count as occult detectives. This version of the history excludes relevant fiction by important writers such as E.T.A. Hoffman, Fitz-James O’Brien, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, and Charlotte Riddell. As I say, perhaps this is prompted by Cohen’s historical parameters. Nonetheless, a quick acknowledgement of literary precedents — as he elsewhere makes with Poe, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, and Wilkie Collins — would have kept me from wincing.

Clear Prose (with a Few More Winces)

Despite that quibble, which might be a very personal one, Cohen writes with a clarity that doesn’t sacrifice intelligence. He builds on the work of several literature scholars, but avoids the specialized jargon that sometimes accompanies discourse in that field. On the other hand, my wincing reflex was also triggered by obsolete terms such as “mulatto” (pg. 22), “negro” (pg. 55), or even “Scotchman” (pg. 64), none of which are clearly signaled as reflecting the language of the era under discussion. Readers forewarned of these moments are likely to find The Golden Era of Sherlock Holmes and His Contemporaries very enlightening.

— Tim