A Headstrong Skull

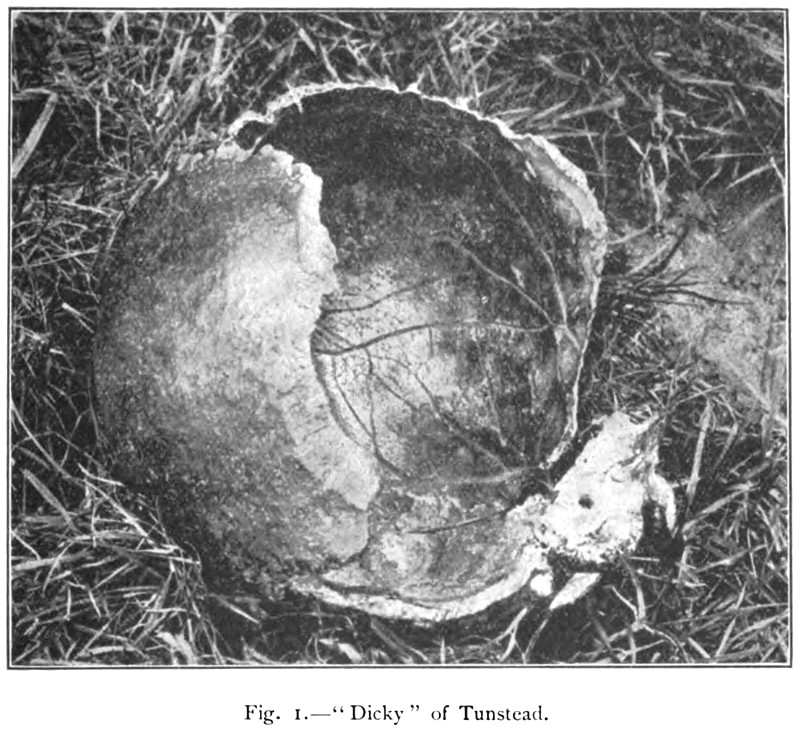

Once upon a time, a folktale circulated in Derbyshire, England. The story was set in Tunstead, a bit south of the midpoint between Whaley Bridge and Chapel-en-le-Frith. Apparently, a local farmer kept a skull on the premises. It was a real skull, mind you! There are pictures! Exactly why the farmer had it is less certain. Back when the skull’s original user — named “Dicky” or “Dickey,” depending on the source — had been buried, her or his — sources disagree on the gender — ghost grew unhappy. That spirit created a ruckus involving wailing sounds, knocked-about furniture, and wandering and dying cows. Somehow, it was determined that keeping the skull on the farm kept said spirit quiet and content. In fact, “it” protected the place against theft.

And so the skull remained on the farm for many decades — without showing the slightest sign of decomposition!

At least, that’s what was said. Seemingly, the earliest written record of the oral tale is found in an 1809 book titled Tour through the Peak of Derbyshire, by John Hutchinson. Unfortunately, I haven’t found a scan of this rare work online. Hutchinson is referenced, though, in an 1862 book titled Tales and Traditions of the High Peak, by William Wood — and there’s a transcription of that here.

Wood’s book probably had a hand in shaping a railroad haunting involving the skull, given that the work had been published just one year earlier. You see, in 1863 — when Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway workers ran into trouble while laying tracks for a line from Whaley Bridge down to Buxton — they had a persnickety ghost nearby upon whom to place the blame.

To be sure, Llewellyn Jewett’s “An Address to ‘Dickie,” one of the best written records of the folktale, was published in 1867 and includes a mention of the railroad workers’ trouble with the headstrong spirit. The same year, William Bennet shared his findings regarding the skull’s origins. He also notes the railroad encounter, suggesting that it had become a fixed part of the lore by then.

From Tale to Rail

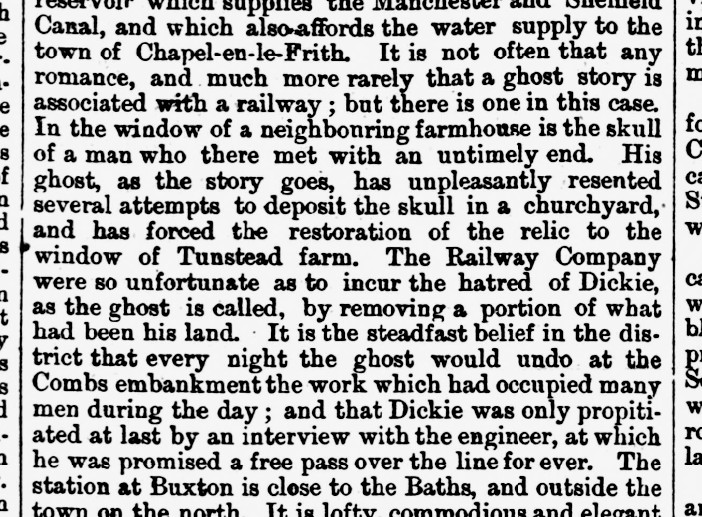

The June 3, 1863, issue of the Derby Mercury reported that the new Whaley Bridge to Buxton line had been opened — but only after considerable difficulty in laying the tracks. (A scan of the original is here for free, but sign-up is required.)

About two miles and a half from Whaley Bridge the line crosses the head of the Combs Valley, near the reservoir which supplies the Manchester and Sheffield Canal, and which also affords water to Chapel-en-la-Frith. Here, for about a quarter mile, the engineer, Mr. A. C. Crosse, met with the greatest difficulty. It was necessary to construct a bridge beneath which the road from Combs to Chapel might pass. The navvies dug through scores of feet of clay resting upon sand, but could find nothing upon which to build a foundation. The earth also of which the embankment was to be made forced outward the surface of the ground, and made it bulge to a remarkable extent. Finally, the Company were compelled to abandon the construction of the bridge and to build another upon the nearest solid ground that they could find. This has necessitated a considerable diversion of the highroad.

While there’s no mention of the ghost in that article, there is in an otherwise almost identical one that appeared two days later in the Nottinghamshire Guardian:

It appears newspaper editors disagreed on whether or not to include the tidbit about the fussy phantom. Yet that tidbit garnered national attention when a London publication called The Panorama reprinted it as “A Railway Ghost” in its Oddities section. To be sure, in 1863, railroad hauntings were a novelty. It took a few decades for musty old ghosts to climb aboard those shiny, newfangled trains, something I discuss in my introduction to After the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore.

Tracking the Ghost Today

Sadly, the skull appears to have gone the way of all flesh. It can no longer be visited, in other words. But its curious history still sparks interest. Darcus Wolfsom did some spook snooping for a site called Explore Buxton, and there you can see another picture of the skull provided by that town’s Museum and Art Gallery. Since Dickie’s range of ghostly activity seems to have been wide and uncertain, focusing on the railroad encounter might help any paranormal investigators interested in the spot.

Indeed, if the present railroad winding from Whaley Bridge Station down and over to Chapel-en-le-Frith reflects the specter-diverted 1863 line, the stretch of tracks west of the Combs Reservoir provides a rough idea of where the ghostly protest was probably made all those years ago. The Combs Reservoir Railway Bridge might serve as a nice starting point, and from there, one can follow a footpath south between Meveril Brook and the reservoir itself. These serve as safe alternatives to actually walking the dangerous tracks. As always, if you do conduct an investigation, be it formal or informal, please give us a report.

And remember that Dickie was appeased with an offer of eternal free rides along those tracks. Maybe the best way to have an otherworldly encounter, then, is by riding the train.