“My name is Sherlock Holmes. … Possibly it is familiar to you. In any case, my business is that of every other good citizen—to uphold the law.”

— “Shoscombe Old Place”

A Dreadful “What If?”

Look. Far be it from me to cast aspersions upon a fictional character with the respect and admiration of Sherlock Holmes. I imagine many of us like to envision him as close to how he describes himself in the epigraph above: a loyal and true defender of English law and order. Riiiiiiight?

Well, as I was reading Arthur Conan Doyle’s “canon” of Holmes adventures, I couldn’t help but notice the occasional flirting with the prospect of the great detective being an outlaw. I was also surprised by the multiple times he breaks the law to resolve a case.

Let’s start with those passages in which Holmes’s astounding abilities prompt those around him—as well as himself—to wonder what if the man with so much insight into crime had, indeed, led a life thereof:

“… I could not but think what a terrible criminal [Holmes] would have made had he turned his energy and sagacity against the law instead of exerting them in its defence.”

— Dr Watson, The Sign of the Four

“It is a mercy that you are on the side of the force, and not against it, Mr Holmes.”

— Inspector Gregson, “The Greek Interpreter”

“You know, Watson, I don’t mind confessing to you that I have always had an idea that I would have made a highly efficient criminal.”

— Sherlock Holmes, “Charles Augustus Milverton”

“It is fortunate for this community that I am not a criminal.”

— Sherlock Holmes, “The Bruce-Partington Plans”

Crossing the Crooked Line

And then there are those times when, in fact, Holmes sidesteps (to put it gently) the law as a means to attain the greater good (to put it idealistically). He even exerts a corrupting influence on his faithful companion.

“You don’t mind breaking the law?”

“Not in the least.”

Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson, “A Scandal in Bohemia”

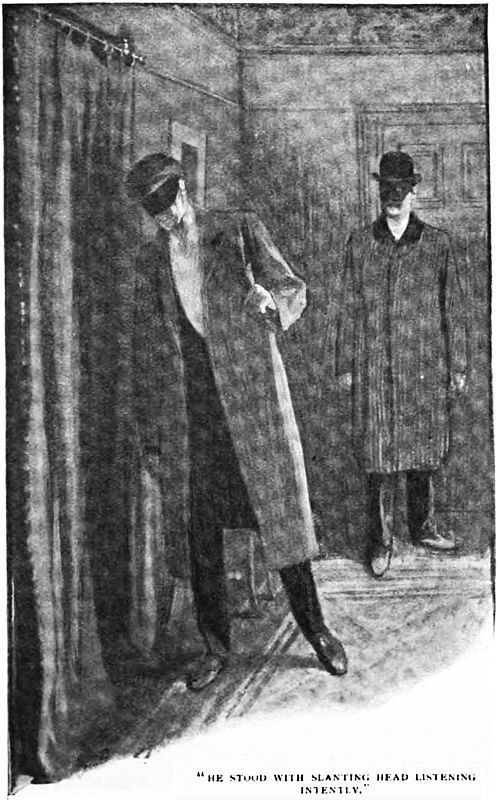

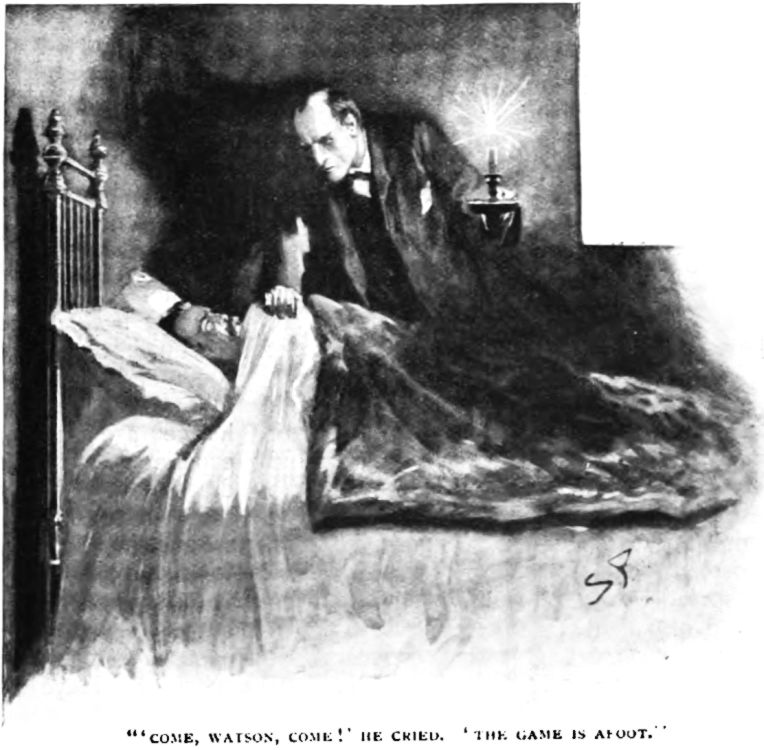

“Watson, I mean to burgle Milverton’s house tonight.”

— Sherlock Holmes, “Charles Augustus Milverton” [and Watson again joins him]

“I have been three times in [Moriarty’s] rooms, twice waiting for him under different pretexts and leaving before he came. Once—well, I can hardly tell about the once to an official detective. It was on the last occasion that I took the liberty of running over his papers. …”

— Sherlock Holmes to Inspector MacDonald, The Valley of Fear

“My dear fellow, you shall keep watch in the street. I’ll do the criminal part. It’s not a time to stick at trifles.”

— Sherlock Holmes to Dr Watson, “The Bruce-Partington Plans”

“Sherlock Holmes was threatened with a prosecution for burglary, but when an object is good and a client is sufficiently illustrious, even the rigid British law becomes human and elastic.”

— Dr Watson, “The Illustrious Client”

“… I suppose I shall have to compound a felony as usual.”

— Sherlock Holmes, “The Three Gables”

“There being no fear of interruption I proceeded to burgle the house. Burglary has always been an alternative profession, had I cared to adopt it, and I have little doubt that I should have come to the front.”

— Sherlock Holmes to Inspector MacKinnon, “The Retired Colourman”

Not only does Holmes commit crimes, he admits as much—even to officials of Scotland Yard! (He seems especially comfortable doing so when said official has a Scottish surname. What’s that about?) Maybe this is partly explained by Holmes’s deep immersion into criminal behavior, which has tainted his worldview. In “The Copper Beeches,” while sharing a train ride with Watson, he admits he’s unable to enjoy watching the countryside go by:

[I]t is one of the curses of a mind with a turn like mine that I must look at everything with reference to my own special subject. You look at these scattered houses, and you are impressed by their beauty. I look at them, and the only thought which comes to me is a feeling of their isolation and of the impunity with which crimes may be committed there.

Accordingly, Holmes sees a crime where there is no crime in both “The Yellow Face” and “The Lion’s Mane.”

And Watson seems a tad eager to fall in with the felonious fun. Without hesitation, the doctor joins Holmes in attempted burglary in “A Scandal in Bohemia.” In “Charles Augustus Milverton,” he raises only the flimsiest objections before telling Holmes that he “will take a cab straight to the police-station and give you away unless you let me share this adventure with you.” Even when Holmes is elsewhere, Watson partners with Sir Henry Baskerville in “aiding and abetting a felony,” to use the words of Sir Henry himself, by looking askance as arrangements are made to help a prison-escapee nicknamed the Notting Hill murderer flee the country. Perhaps lurking in the back of Watson’s mind is something Holmes says in “The Speckled Band”: “When a doctor goes wrong he is the first of criminals. He has nerve and he has knowledge [to commit murder by poison].” Did Watson hear this and begin to have very impure thoughts? Does this provide a glimpse into the disappearance of Mary, his wife?

An Era of Criminal Fog?

If asked for my favorite story now that I’ve finished the canon, I would go with “Charles Augustus Milverton.” It’s as if Doyle ached to write a story in which almost every character does something very naughty, if not blatantly illegal. The client has done something bad enough that the title character is blackmailing her. As a last resort, Holmes and Watson break into Milverton’s house to retrieve the incriminating letter. Remember, if the two are caught, the harm to their reputations might destroy their careers as detective and doctor! In the middle of this crime, our heroes stumble upon another very unexpected one, which they shrug off about an hour or two afterward. (Hey, Milverton was a wanker anyway.) In the end, Lestrade stands tall as the unblemished character, even though he fell short by, well, afoot of capturing those two masked dudes sneaking around Milverton’s house.

I’m left asking what thoughts regarding crime were swirling around when the Holmes tales were debuting. This is the time frame I used to select the fiction found in the Curated Crime Collection, all of which illustrates how difficult it sometimes can be to distinguish legal from illegal, moral from immortal, and good from bad. These blurred lines seem to have held a particular interest for many readers of the late-Victorian and Edwardian eras.

Then again, stories about crime have been around long before those decades, and they persist afterward. Yes, fictional criminals are far from confined to the late 1800s and early 1900s. Perhaps, something like Holmes, “I must look at everything with reference to my own special subject.”

— Tim