*Trusted Archival Research Documents in Sequence

Investigating the death of Edgar Allan Poe can sink a person deeper and deeper into the murky waters of mystery. Here, I attempt to present some of the evidence of the case. When testimony was given many years after the fact, I mark the date as “in hindsight” to suggest that the evidence there might have been tainted by time.

1849

Monday, July 2 or 9, in hindsight

In John Sartain’s 1899 autobiography, The Reminiscences of a Very Old Man, the artist/magazine editor addresses his final encounter with Poe in Philadelphia. (A truncated version, titled “Reminisces of Edgar Allan Poe,” had appeared in Lippincott’s in 1889.) Sartain says that, in 1849, “one Monday afternoon he suddenly entered my engraving-room, looking pale and haggard and with a wild expression in his eyes.” Sartain recalls Poe begging for refuge and then explaining his predicament:

[H]e told me that he had been on his way to New York, but he had overheard some men who sat a few seats back of him plotting how they should kill him and then throw him off from the platform of the car. He said they spoke so low that it would have been impossible for him to hear and understand the meaning of their words, had it not been that his sense of hearing was so wonderfully acute.

Next, Poe said he evaded his assassins by stealthily detraining at Bordentown, New Jersey, and catching the next train back to Philadelphia. Asked why the men would want to kill him, Poe said it was revenge for “a woman trouble.” Sartain concludes the anecdote by saying Poe left a few days later, having regained a clearer state of mind.

Sartain doesn’t provide a precise date for this encounter, probably due to his recalling events from decades earlier. However, he offers a rough guess in a concluding comment: “In about a month from this, as near as I can make out, Poe lay dead in a Baltimore hospital.” In Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography, Arthur Hobson Quinn says Poe’s arrival at Sartain’s door “would have been July 2nd, or July 9th” (pg. 615). In Edgar Allan Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance (1991), Kenneth Silverman cautiously calculates the date to be “seemingly July 2” (pg. 416).

Saturday, July 14

In a letter with this date, Poe tells Maria Clemm, his beloved aunt/mother-in-law, that he has arrived in Richmond (presumably having departed Philadelpha the day before). He says:

I am so ill while I write — but I resolved that come what would, I would not sleep again without easing your dear heart as far as I could. … My clothes are so horrible, and I am so ill.

The mention of his clothes is interesting, given how it foreshadows how he will be found dressed on October 3. Regarding his health, though, in a letter dated July 19, 1849, he tells Clemm: “I am much better — much better in health and spirits.”

Wednesday, August 29

In a letter with this date, Poe wrote to Clemm about his status with Sarah Elmira Royster Shelton, a love interest rekindled from two decades earlier. He says the two “are solemnly engaged to be married within the coming month.” Poe adds: “Her relations — her married daughter especially — are opposed to it — because their pecuniary interests will be injured — but she defies them & seems resolved.” Indeed, Poe presents several impressive figures to indicate Shelton’s income. Was her wealth part of the appeal for Poe?

Then Poe says something interesting, if not downright disconcerting:

[T]here is one other thing, too, dear mother, which drives me frantic — my love for Annie — I worship her beyond all human love. My passion for her grows stronger every day. I dare not, at this crisis, either speak or think of her — if I did I should go mad — but oh Muddy, if you have ever loved your son, do not — do not let my Annie have hard thoughts of me.

“Muddy” is Poe’s nickname for Clemm, and “Annie” refers to Nancy Richmond, a married woman living in Massachusetts and the inspiration for his poem “To Annie.”

Tuesday, September 18

In a letter with this date, Poe informs Clemm of his intention to return to Philadelphia and “attend to Mrs. [Marguerite St. Leon] Loud’s Poems — & possibly on Thursday I may start for N. York.…” He urges Clemm to write to him in Philadelphia, adding: “For fear I should not get the letter, sign no name & address it to E. S. T. Grey Esq[ui]re.” It is unknown why Poe felt the need for a pseudonym.

(The poems Loud presumably wanted Poe to polish were collected in Wayside Flowers, published in 1851.)

Wednesday, September 26, in hindsight

In “Edgar Poe’s Last Night in Richmond,” an article in the November, 1902, issue of Lippnincott’s, Dr. John Carter says that Poe paid him a visit on this evening. This corroborates what Susan Archer Weiss had said in “The Last Days of Edgar Allan Poe” in the March, 1878, issue of Scribner’s. Carter himself, though, is presumably the better witness for what follows. The physician says:

On this evening [Poe] sat for some time talking, while playing with a handsome Malacca sword-cane recently presented me by a friend, and then, abruptly rising, said, ‘I think I will step over to Saddler’s [a popular restaurant in the neighborhood] for a few moments,’ and so left without any further word, having my cane still in his hand. From this manner of departure I inferred that he expected to return shortly, but did not see him again, and was surprised to learn next day that he had left for Baltimore by the early morning boat. I then called on Saddler, who informed me that Poe had left his house at exactly twelve that night, starting for the Baltimore boat …, and giving as a reason therefor the lateness of the hour and the fact that the boat was to leave at four o’clock. According to Saddler he was in good spirits and sober, though it is certain that he had been drinking and that he seemed oblivious of his baggage, which had been left in his room at the Swan Tavern. These effects were after his death forwarded … to Mrs. Clemm in New York, and through the same source I received my cane, which Poe in his absent-mindedness had taken away with him.

Thursday, September 27

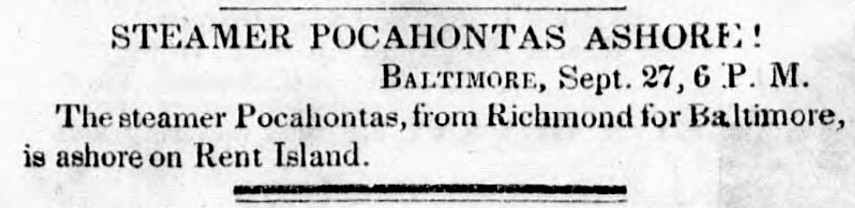

Poe left Richmond, Virginia, on a ship heading to Baltimore. Many sources put his arrival on Friday, September 28, and some suggest he sailed on the Pocahontas. This announcement in the September 28 issue of the Daily Richmond Times indicates that a steamship with this name had made it as far as Chesapeake Bay’s Kent Island (not Rent Island) by Thursday evening:

Scroll down to the “1849 (Sept. 28)” entry on this Chronology of Poe in Baltimore for more about the disagreements over the final time Poe arrived in that city.

Wednesday, October 3

Joseph W. Walker discovered Poe, semi-conscious and disheveled, near or in an establishment going by the name of Ryan’s Hotel and by 4th Ward Hotel. (Gunners’ Hall was a part of it, a room that seems to have been used for political meetings and/or for drinking.) On Poe’s instruction, Walker sought assistance from Joseph E. Snodgrass, an editor with some medical training. Walker’s message, it seems, remained in the possession of Snodgrass’s wife, and a copy of it is presented in the Biography volume of Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, edited by James A. Harrison and published in 1902. It reads:

Baltimore City, 3rd, 1849

Dear Sir, — There is a gentleman, rather the worse for wear, at Ryan’s 4th ward polls, who goes under the cognomen of Edgar A. Poe, and who appears in great distress, and he says he is acquainted with you, and I assure you he is in need of immediate assistance.

Yours in haste,

JOS. W. WALKER

The message had been published earlier in George Edward Woodberry’s 1885 biography of Poe, where it is attributed to the March 27, 1881, issue of New York Herald.

In hindsight:

In a letter to Women’s Temperance Paper, probably published in late 1855 or very early 1856, Snodgrass discusses what happened after he received Walker’s message. This source appears to be no longer extant, but the title is significant because Snodgrass was shaping Poe’s story to illustrate the tragedy of drinking alcohol. Fortunately, the piece was reprinted under the title “E.A. Poe’s Death and Burial” on page 155 in the January 26, 1856, issue of Spiritual Telegraph. (There’s a transcription of it here.) Along with presuming Poe to be “in a deep state of intoxication,” Snodgrass introduces some discrepancies, such as dating the event in November instead of October. Nonetheless, he provides a potentially significant clue when he describes what he found:

I instantly recognized the face of one whom I had often seen and knew well, although it wore an aspect of vacant stupidity which made me shudder. The intellectual flash of his eye had vanished, or rather had been quenched in the bowl; but the broad, capacious forehead of the author of “The Raven,” … was still there, with a width, in the region of ideality, such as few men have ever possessed. But perhaps I would not have so readily recognized him, had I not been notified of his apparel. His hat — or rather the hat of somebody else, for he had evidently been robbed of his clothing or cheated in an exchange — was a cheap palm-leaf one, without a band, and soiled; his coat of commonest alpacca [sic], and evidently ‘second hand;’ and his pants of grey-mixed cassimere, dingy, and badly fitting. He wore neither vest nor neckcloth, if I remember aright, while his shirt was sadly crumpled and soiled.

From here, says Snodgrass, Poe was “placed in a coach, and conveyed to the Washington College Hospital.” He slightly misremembered the name of the hospital, identified as Washington University Hospital in this 1846 newspaper article and this 1849 report. Snodgrass retells this story in “The Facts of Poe’s Death and Burial,” published the March, 1867, issue of Beadle’s Monthly.

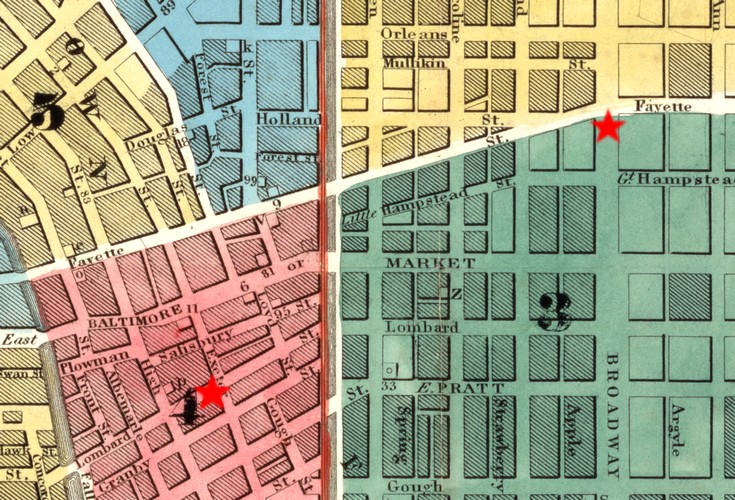

The long-gone tavern was on Lombard Street, between High and Exeter. The hospital later became Church Home and Hospital, and the building can still be seen on Broadway near Fayette. This c. 1844 map provides a view of the distance between where Poe was found disoriented and disheveled, and where he died four days later.

Saturday, October 6, in hindsight

In a letter dated November 15, 1849, and addressed to Maria Clemm, Dr. John Joseph Moran, who attended to Poe at the hospital, explains:

I found [Poe] in a violent delirium, resisting the efforts of two nurses to keep him in bed. This state continued until Saturday evening (he was admitted on Wednesday) when he commenced calling for one “Reynolds”, which he did through the night up to three on Sunday morning.

In a 1987 article titled “Dr. Moran and the Poe-Reynolds Myth,” W.T. Bandy charts how Poe biographers have treated the letter’s tantalizing clue. He points out that Moran recounted his experience with Poe for publication in 1875 and 1885, changing his claim about Poe calling for Reynolds. Bandy then argues that “Reynolds was only a figment of Moran’s imagination” and explains that, over time, the doctor replaced “Reynolds” with “Herring,” the name of Poe’s relative living in Baltimore. The reference in the letter, then, “was just a mistake on Moran’s part, which he gradually corrected. We would therefore waste time to speculate further on the identity of Reynolds.” If Bandy is correct, then “Reynolds” is a red herring. Of course, there are other possibilities as to why Moran changed his story over time.

Sunday, October 7

Edgar A. Poe died at Washington University Hospital.

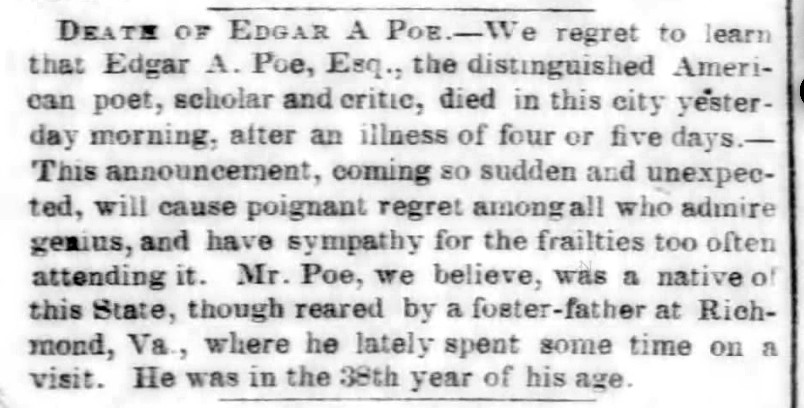

Monday, October 8

The following death notice appeared in The Baltimore Sun:

In the days to follow, the news spread from Washington D.C. to at least as far west as Louisiana and Wisconsin.

Tuesday, October 9

In contrast to the kind words expressed in The Sun, an uglier picture is painted in another obituary published a day afterward. It appeared in the New York Daily Tribune, and though signed “LUDWIG,” it has been attributed to Rufus Griswold. The article opens by saying that “few will be grieved by” Poe’s passing. Though internationally admired, the author “had few or no friends….”