*Trusted Archival Research Documents in Sequence

1756-1757?

A pamphlet published in 1762 says William Kent married Elizabeth Lynes in 1756. However, “about eleven months after their cohabitation,” the wife died. Unless they had married in January, then, the death was in 1757. The pamphleteer argues on the side of Kent’s innocence, but there’s little reason to think this date somehow reflects this bias. (Much later, this anonymous pamphlet was attributed to Oliver Goldsmith.)

1760? (The events of this year are dubious because they were claimed in 1762 by those later convicted for fraud.)

According to the January 1762 issue of Universal Magazine, pp. 45-48, “About two years since [meaning two years ago], a publican in the neighborhood” of Cock Lane was terrified upon seeing “a bright shining figure of a woman” at the Parsons’ residence. Parsons also saw it “within the space of an hour.” Parsons’ daughter Elizabeth is reported to have seen an apparition, too, but the timing of her sighting is vague: “some time ago.” The girl identifies her apparition as Francis “Fanny” Lynes.

It’s more certain that, in 1759-1760, Lynes had been posing as William Kent’s wife as the two lodged at the Parsons’ house. Curiously, in the January 1762 issue of Gentleman’s, pp. 43-44, Elizabeth is said to have shared a bed with Lynes “about two years ago,” at which time a ghostly “knocking was first heard” by the two. If Lynes was alive at that point, whose ghost had knocked? Young Elizabeth Parsons answers this question by saying it was that of Elizabeth Kent, Lynes’ sister and Kent’s lawfully wedded wife. As noted above, Elizabeth Kent had died around 1757.

1762

January

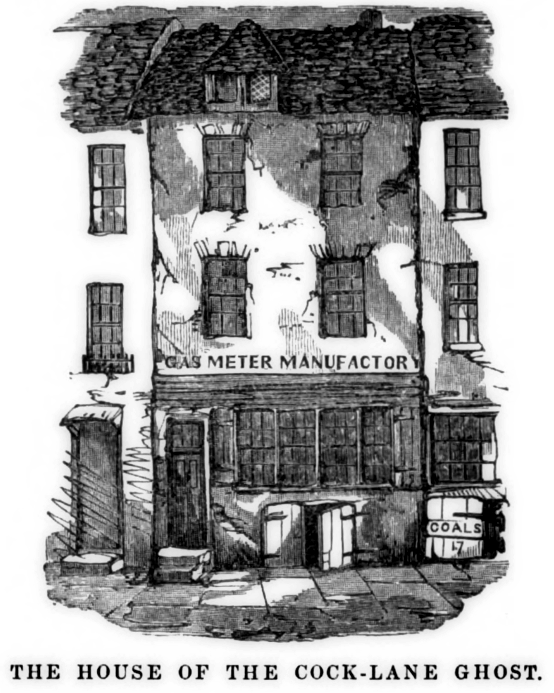

According to Douglas Grant (p. 25), the news about a ghost manifesting at the Parsons’ residence on Cock Lane — and, via knocking, accusing William Kent of its murder! — originally appeared in London’s newspaper The Public Ledger. The series of articles seems to be unavailable in either physical or digital form. (The researcher who discovers otherwise wins big!) Fortunately, other London newspapers and magazines helped themselves to the news.

This month, Gentleman’s Magazine, pp. 43-44, reports on a January 13th investigation and recaps the story to date: a ghost manifesting “through” young Elizabeth Parsons started communicating by knocking once for yes and twice for no. In the process, the ghost identified itself as Francis Lynes and accused William Kent of having murdered her. London Magazine, pp. 50-52, recaps the story and discusses the preliminaries of a February 1 investigation, to be led by Stephen Aldrich. Universal Magazine, pp. 45-48, gives a substantial account of the story to date. The story reviews incriminating claims made against Kent beyond those of the ghost. It includes information on investigations held on January 20th and 22th, and on the arrangements for the one to be held on February 1.

February

In a letter dated February 2, 1762, aristocrat and man of letters Horace Walpole describes a visit to the Parsons’ residence, which the media coverage had turned into a popular attraction:

[I]t rained torrents; yet the lane was full of mob, … and the company squeezed themselves into one another’s pockets to make room for us. The house which is borrowed, and to which the ghost has adjourned, is wretchedly small and miserable; when we opened the chamber, in which were fifty people, … we tumbled over the bed of the child, to whom the ghost comes, and whom they are murdering by inches in such insufferable stench and heat.

This month’s issue of Gentleman’s Magazine, pp. 81-82, prints Samuel Johnson’s firsthand account of the February 1 investigation. No knocks were heard near Elizabeth. The ghost, who had previously promised to confirm its identity by knocking on Lynes’ coffin, failed to do so at St. John’s burial vault. The ghost-hunting team combined this, well, lack of evidence to conclude that “the child has some art of making or counterfeiting particular noise, and there is no agency of any higher cause.” London Magazine, pp. 103-04, recaps Johnson’s report and then condemns the continuing belief in the ghost. Universal Magazine, pp. 101-03, repeats Johnson’s report and ends with a parody of the case.

March

This month’s issue of London Magazine, pp. 150-53, reports that Elizabeth Parsons was still being put in beds in various houses in the hope that the ghost might manifest near her. Results were spotty. The article ends by saying that Kent — to prove that he hadn’t moved Lynes’ body shortly before the February 1 investigation to prevent her ghost from knocking on it — joined a party to confirm that she was still in the St. John’s crypt. The corpse was still there, “and a very awful shocking sight it was.” It then quotes extensively from The Mystery Revealed. As noted above, this pamphlet was probably written by Goldsmith and is designed to stir sympathy for Kent.

July

The July 10-13 issue of London Chronicle, p. 42, announces the July 10th guilty verdict passed on Parsons and others “for a conspiracy in the Cock-Lane Ghost affair.” Here, the plaintiffs are clearly identified as “Richard Parsons” and “William Kent” while, in the articles mentioned above, identities are protected with phrases such as “one Parsons” and “Mr. K—.”

1763

In late March, the London Chronicle makes a quick mention of Parsons standing on the pillory. He was “treated with great humanity, and several of the spectators gave him money.” The entire case is recapped in The Annual Register, or A View of the History, Politicks, and Literature of the Year 1762, pp. 142-47. Here, we learn the specifics of the sentences imposed on those involved. Again, the curious reaction to Parsons on the pillory is mentioned: “the populace took so much compassion of him, that, instead of using him ill, they made a handsome collection for him.”

Reinterpretations of the Case

Why would someone have perpetrated such an elaborate hoax? For a long time, it was thought that, because Kent had sued him for money owed, Parsons held a grudge and orchestrated the hoax to hurt Kent’s reputation. In a 1766 book titled A New and Accurate History and Survey of London, Westminster, Southwark, and Places Adjacent, John Entick describes the affair as “a wicked contrivance to be revenged on Mr. K—t for suing for a trifle of money” (p. 205). Pointing to this motive to explain the hoax persisted for over a century. In an 1871 book titled The Book of Remarkable Trials and Notorious Characters, Captain L. Benson offers some in-depth mindreading of a man long dead. Benson says that, even though two years had passed:

Parsons was of so revengeful a character, that he had never forgotten or forgiven his differences with Mr. Kent, and the indignity of having been sued for the borrowed money. The strong passions of pride and avarice were silently at work during all that interval, hatching schemes of revenge, but dismissing them one after the other as impracticable, until, at last, a notable one suggested itself. (p. 166)

That notable scheme, of course, was the ghost hoax.

1868

Along the way, new theories were introduced. For instance, in the mid-1800s, Spiritualism burst on the scene with its entranced mediums conveying messages from the dead at séances. Given the parallels between this and Lynes communicating when young Elizabeth Parsons was, at least, drowsy in bed, it was a small step for William Howitt to defend the ghost’s authenticity in an 1868 issue of The Spiritual Magazine (p. 202), a publication devoted to promoting Spiritualism. He explains that the failure of Lynes’ spirit to make its presence known near her coffin was because Aldrich’s investigation team “did not take the little girl with them, and not having the medium, they of course had no manifestation.” He concludes that “a careful examination of this story by modern lights, and the rules of regular evidence, have only tended to prove that the manifestations of the ghost were genuine enough.” Thus, a new wave of believers brought the ghost back to life.

1908

Then rose psychoanalytic theory, led by Sigmund Freud, in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Psychical researchers borrowed some of these ideas and applied them to hauntings, especially poltergeist phenomena. See, for instance, Walter Prince’s 1922 evaluation of a case in Nova Scotia. Interestingly, in a 1908 book called Historic Ghosts and Ghost Hunters, H. Addington Bruce suggests that, had Prince or someone like him been present at Cock Lane in 1762, he could have resolved the matter. This is because Elizabeth Parsons’ father wasn’t to blame for the hoax—no, due to “the uncontrollable impulses of a hysterical child,” the burden rests on Elizabeth herself. Bruce hypothesizes that Lynes’ death so traumatized the girl that her

disordered consciousness would conceive the idea that her friend had been murdered and that it was her duty to bring the slayer to justice. From this it would be an easy step to the development, in the neurotic child, of a full fledged secondary personality, akin to that found in the spiritistic mediums of later times. (pp. 99-100)

As did Captain Benson before him, Bruce draws some wild conclusions about the psyche of a person whose ghost was not around to affirm or refute the allegations.