INTRODUCTION

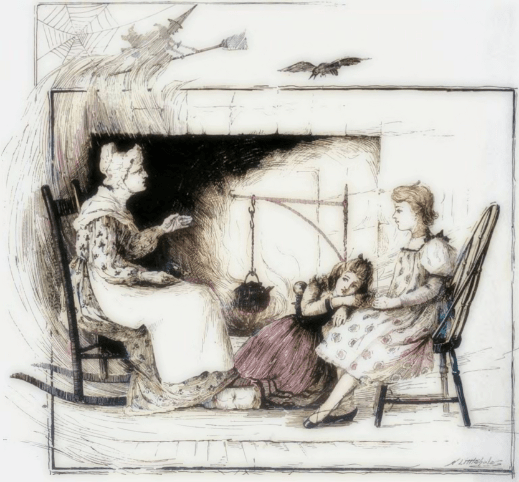

Once upon a time, perhaps while gathered around a fire, people told tales about witches and those who hunted them. These folktales, passed along orally, tantalized yet terrified listeners. The stories weren’t aimed at children alone, and adults probably recognized that they were primarily for amusement.

As literacy rose in the 1800s, more and more scholars followed the example of Jacob and Wilhem Grimm by transcribing such tales, preserving them on paper. Very likely, these were “loose” transcriptions. In some cases, the transcriptions were translated into English. Very likely, these were “loose” translations.

Around the early 1900s, some of these transcriptions and translations were revised to take advantage of a growing market for children’s literature. Most definitely, these were “loose” adaptations, as seen when comparing the Grimm Brothers’ version of Cinderella — with its stepsisters slicing off chunks of their feet to fit the golden (not glass) slipper — to the much less bloody Disney movie version. In one sense, these loose transcriptions, loose translations, and loose adaptations are very much in keeping with oral tradition, which allows its stories to evolve and adapt with every renewed telling.

“Whispers of Witchery: Exploring Written Records of Witch and Witch Hunter Folktales” is an ongoing project that delves into this winding history of transcription, translation, and adaptation. As my research progresses, I will expand this main page, organizing and summarizing specific legends and fables. I will also provide links here to historical written records of each folktale as well as to my own posts regarding them.

LOCAL LEGENDS

England

CORNWALL: Carn Kenidjack is an eerily beautiful outcropping not too far from Penzance. The formation has inspired several legends about supernatural events and beings, but one involves a witch named Old Moll. Transcribed by Robert Hunt and published in 1865, the brief folktale illustrates how a witch’s power sometimes lingers beyond death. My comments are here.

LEICESTERSHIRE: Lurking in a cave somewhere in the Dane Hills and called Black Annis or Black Anna, a bloodthirsty and flesh-hungry witch threatened both livestock and children in the region. Her face was blue, and instead of hands, she had talons (or perhaps nothing more than poorly trimmed fingernails). Two key sources of information on this legend are John Heyrick’s poem “On a Cave Called Black Annis’s Bower,” published in 1797, and a section titled “Caves” in Charles James Billson’s “Leicestershire & Rutland,” published in 1895. My survey of relevant records is here (along with my observation that Black Annis wasn’t termed a witch until around 1900).

LINCOLNSHIRE: The village of Byards Leap derives its name from a legendary horse. Feeling the stab of an evil witch’s talon-like fingernails, the steed made an incredible leap, one that played a decisive part in that witch’s death. There’s an impressive number of written records about the oral folk tale, and the details of the narrations vary significantly. I trace key records, ranging from the early 1700s to the early 1900s, and summarize their differences in my comments.

SOMERSET: A stalagmite in the Wookey Hole Caves has a shape suggestive of a witch, and according to local lore, that’s exactly what it once was. A tragic yet troublesome woman was turned to stone when an ecclesiastic witch hunter from Glastonbury sprinkled holy water on her. The tale, transcribed in verse, appears in a 1755 issue of Gentleman’s Magazine. This wasn’t the only explanation for the witchy stalagmite, though. A transcription of a very different folktale was published in 1804. My comments are here.

WEST YORKSHIRE/LANCASHIRE: Long ago, near Todmorden, Lady Sybil became a witch in order to roam the forest in the form of a white doe. Lord William, rejected by Lady Sybil, sought guidance from another witch named Mother Helston. With some magical help, Lord William captured the doe/Lady Sybil. As you do, she renounced witchcraft and married him. But change is hard, and Lady Sybil later transformed into a cat. Renouncing witchcraft yet again on her deathbed, she now appears as a ghost every Halloween. Transcriptions of the legend are found in John Roby’s Traditions of Lancashire (1829), John Harland and T.T. Wilkinson’s Lancashire’s Legends, Traditions, Pageants, Sports, Etc. (1873), T.F. Thiselton Dyer’s Strange Pages from Family Pages (1895), and Joshua Holden’s A Short History of Todmorden (1912). My comments are here.

United States

CONNECTICUT: In the village of Stepney, a woman named Hannah Cranna murdered her husband, Silas. After a long disappearance, she returned to the village with strange powers. When wronged, Hannah cast a curse; when treated well, she used her powers for good. An early transcription of the various folktales about her was published in the Newtown Bee on December 7, December 14, and December 21 of 1900. This article identifies Hannah’s husband as Silas Cranna, but some websites — such as this one, this one, and this one — identify her as the wife of Joseph Hovey. My tally of this and other new twists on the old legend are here.

MAINE: Even today, visitors to Bucksport can see an image of a leg embedded in a cemetery monument for the family of Colonel Jonathan Buck (1719-1795). Legend has it that the leg resulted from a curse cast by a woman condemned for witchcraft by Buck, who is painted to be an obstinate witch hunter. James O. Wittemore’s transcription of the legend, first published in 1898, is here, and my cautions against confusing it with Buck’s actual history are here.

MARYLAND: Some say that, long ago, residents living near what is now Leonardtown labeled Moll Dyer a witch. They drove her off by burning down her home on a frigid night. Days later, Dyer’s frozen corpse was discovered with one hand placed against a rock. That rock carried the imprint of her hand and, some say, the power to bring misfortune to anyone who dares touch it. A rock purported to be the very one is on display today. A transcription of the legend, published in 1892, is here, and my discussion of the story is here.

MASSACHUSETTS: Gloucester is home to a witch legend with interesting details. For instance, it’s set in a specific year: 1745. That’s when a gang of soldiers harassed a woman reputed to be a witch, and another curious detail is her name: Peg Wesson. The legend of how Wesson retaliated is transcribed in John J. Babson’s History of the Town of Gloucester (1860). In 1892, Sarah G. Duley’s creative retelling of the legend appeared in newspapers from Virginia to the State of Washington. My comments are here.

RHODE ISLAND: According to legend, there’s a “witch’s rock” somewhere in the woods covering Hopkins Hill. The boulder marks a patch of land that can never be plowed or otherwise cultivated due to a curse cast by a witch, one who was driven from her home there. A transcription of the legend, published in 1885, is here, and my discussion of it is here.

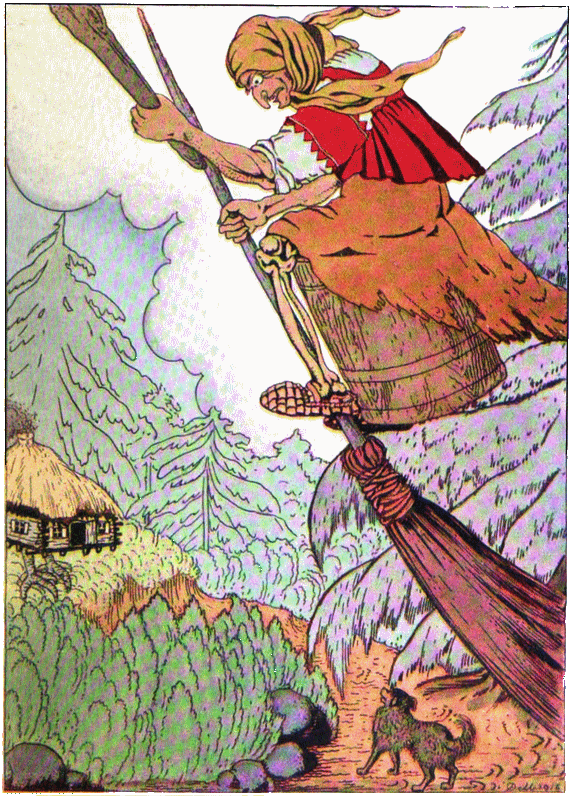

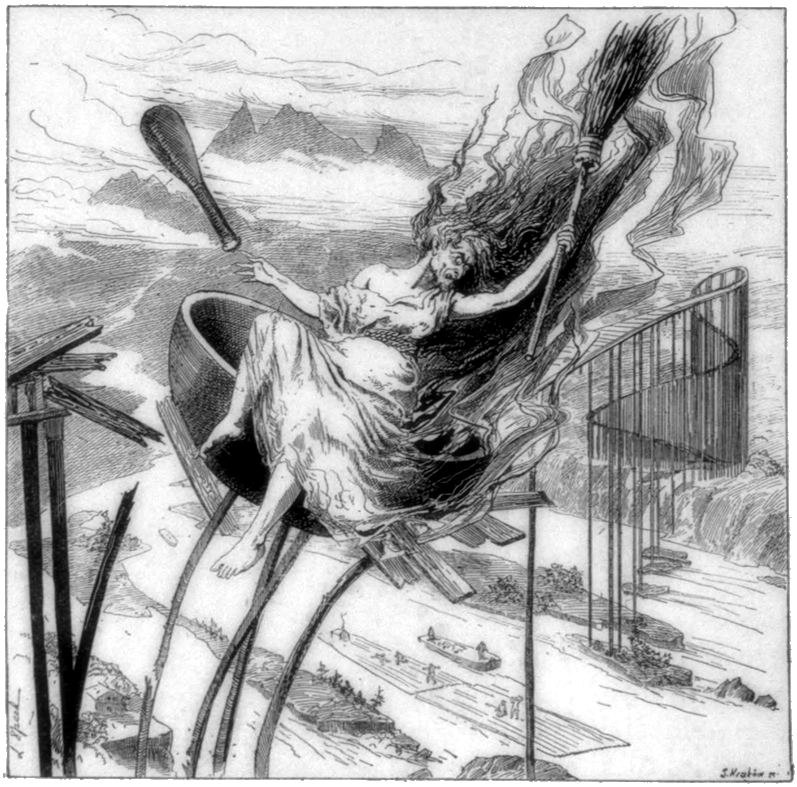

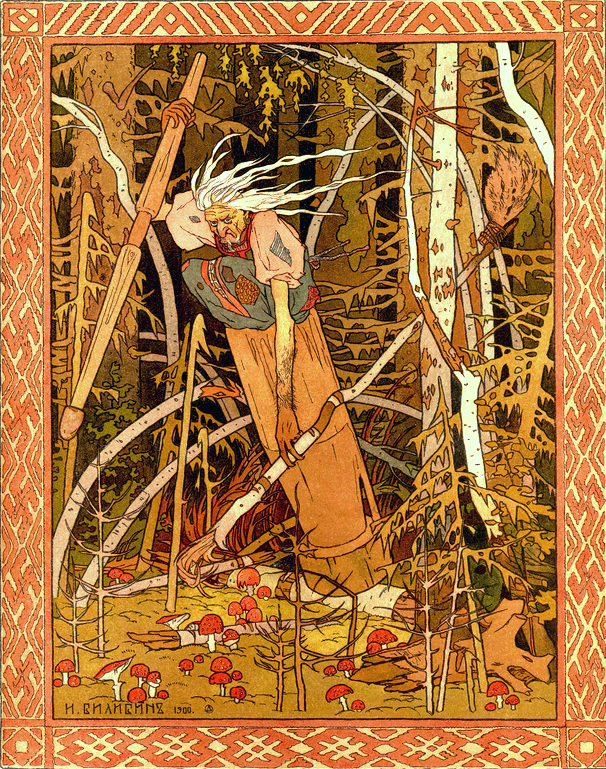

BABA YAGA FABLES

(translated into English)

“The Baba Yaga”: A girl’s kind acts are reciprocated when she escapes the clutches of the Slavic witch figure, Baba Yaga. Alexander Afanasyev’s transcription was translated by W.R.S. Ralston (1873). Scroll down a bit, and you’ll find my discussion of it here.

“The Enchanted Princess”: A soldier frees a princess cursed to be a bear. Afterward, they fall in love, but the the soldier is then cursed and blown far, far away. On his journey back, he is assisted by three Baba Yagas. The last commands the winds to whisk the soldier back to the princess. The tale was translated by Jeremiah Curtin (1890), and it’s the third tale I discuss on a post titled “The Kinder Side of Baba Yaga(s)”.

“The Feather of Bright Finist the Falcon”: Finist, who morphs between falcon and human, is driven away from the maiden he loves. On her quest to find him, the maiden is assisted by three sisters: the Baba Yagas. The tale was translated by Jeremiah Curtin (1890) and by Post Wheeler (1912), though the helpful sisters aren’t identified as Baba Yaga in the latter. It’s the first tale I discuss on a post titled “The Kinder Side of Baba Yaga(s)”.

“The Footless and Blind Champions”: Ivan, accompanied by his faithful tutor, Katoma, travels far to win and marry Anna the Beautiful. Thanks to Katoma, Ivan overcomes the many ploys Anna uses to avoid the marriage, but she still humiliates him by making him a shepherd. Meanwhile, she orders that Katoma be left stuck on a stump with his feet amputated. A very capable blind man comes to Katoma’s aid, and — by besting a vampiric Baba Yaga — the two men coerce the witch to divulge a means to restore their sight and feet. They then return to fix the marital problems of Ivan and Anna. The tale was translated by William Ralston (1873) and by Jeremiah Curtin (1890). I discuss here how this tale helps to show that, even in minor roles, Baba Yaga has sharp contrasts from story to story.

“The Frog-Tsarevna”: The Tsar commands his three sons to marry, and the youngest, named Ivan, winds up with a frog. But it’s no ordinary frog! When Ivan sleeps, she turns into a beautiful woman and does the things the Tsar demands. When Ivan steals his wife’s frog skin, though, she leaves him. On a quest to find her, Ivan comes upon Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged hut. She kindly reveals the secret needed to save his wife from death, which — along with help from forest creatures whose lives Ivan has spared — makes everything dandy again. Alexander Afanasyev’s transcription of the tale was adapted for children by Peter Polevoi and translated by R. Nesbit Bain (1895), translated by Nathan Haskell Dole (1907), and translated by Post Wheeler (1912). I discuss here how this tale helps to show that, even in minor roles, Baba Yaga has sharp contrasts from story to story.

“Marya Morevna”: The great warrior Marya Morevna is kidnapped by Koschei the Deathless. Her husband, Prince Ivan, is unable to rescue Marya because of Koschei’s magical steed. Ivan visits Baba Yaga to get a better horse. In exchange, the witch demands Ivan perform tasks that would have been impossible without the help of animals to which he earlier had been kind. In the end, Ivan steals one of the magic horses, which allows him to rescue Marya and kill Koschei. Along the way, Baba Yaga dies, too. Alexander Afanasyev’s transcription was translated by W.R.S. Ralston (1873), Nathan Haskell Dole (1907), and Leonard A. Magnus (1916). An illustrated reprint of Ralston’s translation — retitled “The Death of Koschei the Deathless” — appears in Andrew Lang’s The Red Fairy Book (1890). My discussion of it is here.

“Vasilissa the Fair” (a.k.a “Vasilisa the Beautiful”): Vasilis(s)a is given a magical doll by her dying mother. Only with its help does the daughter cope with the laborious demands of her cruel stepmother and of Baba Yaga. Alexander Afanasyev’s transcription was translated by W.R.S. Ralston (1873), Nathan Haskell Dole (1907), and Leonard A. Magnus (1916), My discussion of it is here.

“Water of Youth, Water of Life, and Water of Death”: After his two older brothers fail to retrieve rejuvenating water for their father, Ivan tries. Each brother is warned that he faces dismemberments, and the second and third warnings coming from Baba Yaga (or maybe two of them). The bizarre tale was translated by Jeremiah Curtin (1890), and it’s the second tale I discuss on a post titled “The Kinder Side of Baba Yaga(s)”.

“Yvashka with the Bear’s Ear”: In this delightfully twisted tale, a semi-wild boy born with a bear’s ear grows up and, alongside new friends, clashes with the dreaded Baba Yaga. The tale was transcribed and translated by George Borrow (1862). It was also translated by Post Wheeler (1912), and my comments on it are here.