*Trusted Archival Research Documents in Sequence

The term ghost hunt and its derivations ghost hunting and ghost hunter(s) have a fairly impressive history in novels, plays, magazines, and newspapers. I don’t claim to have found the earliest use. It very likely existed in spoken before written English, which means there’s no record, and the longer I investigate the term in print, the farther back I go in time. Plus, who knows how often it was used in publications that have been lost or that, if still extant, have never been digitalized and put online? With these qualifiers, then, I present below much of what I’ve found to date, the key terms in bold.

1794

From Elizabeth Gunning’s novel The Packet:

With a brace of pistols in his pocket, and a sword under his arm, followed by his own man, whom Emeline would not have left out of the ghost-hunting party — thus accoutered, thus attended did Sir William issue from the castle, as soon as he supposed the family were settled for their night’s repose; and, having before procured the original key, he let himself in very softly at the church-door, just as the clock struck one….

It’s established earlier in the novel that, though skeptical, this character is investigating eyewitness reports of a ghost in the church.

1798

An issue of The Scientific Magazine and Freemason’s Repository published a satirical allegory titled “Wisdom and Folly: A Vision.” It mocks novelists, which wasn’t unusual for the period. In the vision, Mrs. Novel is a loyal subject of Queen Folly. Discussing a variety of novelists, the writer turns to those writing Gothic fiction, including Anne Radcliffe and Charlotte Smith, and treats their novels as their children. Moving to “Mrs. Cannon,” the writer says:

She is very prolific:–her children are all loyal subjects to Folly. They are not, however, addicted to the fashionable exercise of ghost-hunting; they satisfy themselves with monsters.

Here, “ghost-hunting” presumably refers to writing in the “fashionable” Gothic genre. (Frankly, through, I’m stumped about who “Mrs. Cannon” is.) The page/article can be found here and here.

1804

In an article on the Hammersmith ghost, a case in which a man shot an innocent man while investigating reports of a ghost, the True Briton reported in its January 6 issue:

The ill-fated man was dressed as usual in his white flannel jacket, and, having parted with his sister at his own door, proceeded along Black Lion lane, where the ghost-hunters were lying in wait.

The same line appears in the January 13, 1804, issue of The Lincoln, Rutland and Stamford Mercury. It also shows up in the January issue of the Universal Magazine of Knowledge as well as that month’s issue of The Scots Magazine. It was common for newspapers and magazines to reprint one another’s articles, and in this case, the term “ghost hunters” was receiving a lot of exposure.

1808

From D. Lawler’s play The School for Daughters:

[…Lucretia approaches the supposed spectre, kneels on one knee, and pronounces, in a solemn tone, the following speech]:

LUC: “Say, thou wandering sprite! that nightly rovest through this solemn scene, say what has called thee from the peaceful tomb, to watch the hours of Cynthia’s silver reign, and scare affrighted mortals?–Nay, shun me not; but stay and speak!

[Jemima throws off the sheet, and bursts out laughing].

LUC. (confounded). How is this!

JEM. (mimicking). Say, thou wandering sprite! what brought thee here a ghost-hunting?

LUC. Ridiculous! I shall die with shame!

1809

In Richard Sicklemore’s novel Osrick; or, Modern Horrors, Lieutenant Osrick Somerton is walking across the downs one night, when he spots a veiled female figure. He approaches to offer assistance, but he sees “a blue flame spread itself about the veil, which it presently consumed, and the lank and fleshless jaws of a skeleton were distinctly to be perceived!” (p. 66). The next night, the Lieutenant and a Mr. Belmont return to investigate the haunted spot. The latter says:

‘…I assure you, this is the first ghost-hunting experience I was ever engaged in.’

On the next page, the two share this exchange:

‘Now, positively, Lieutenant, could you have imagined it possible two days ago?’

‘What?’

‘That such a singular mortal as a ghost-hunter could be heard of in the nineteenth century!’

(My thanks to Michelle McKay for drawing attention to this source.)

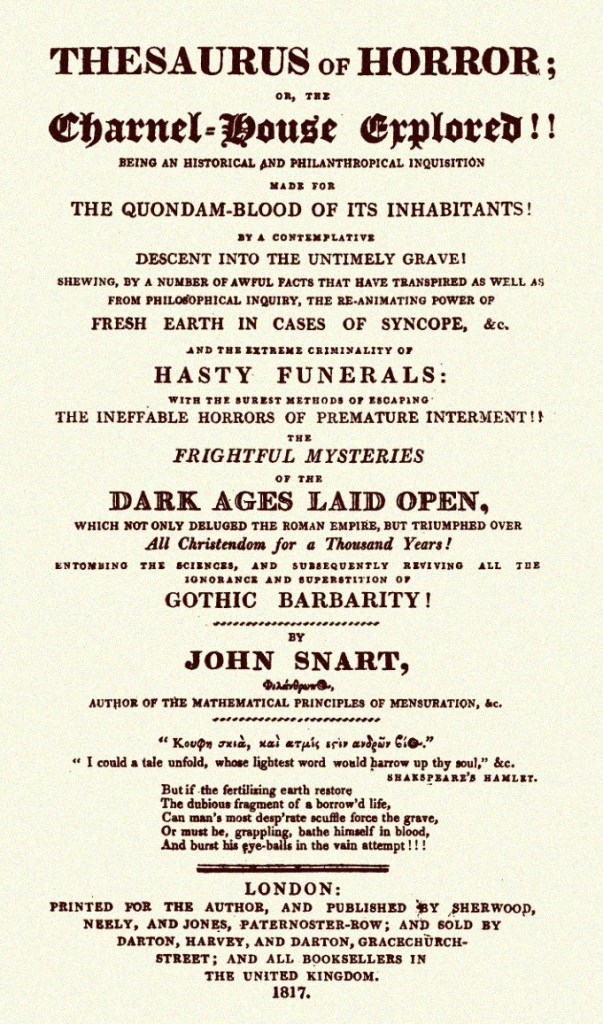

1817

In Thesaurus of Horror; Or, The Charnel-House Explored!!, John Snart announces that his book’s topic is “preservation from the horrors of the grave by premature interment!” (p. 5). He later explains that, to prevent his children from fearing ghosts, “the Writer” (meaning Snart himself) could

always pacify them by the promised treat of ghost-hunting, until they would go alone about the house of an evening with a bottle to catch one, to see it put under the receiver of an air-pump, and be subjected to the pneumatic test instead of a rat,—the natural consequence was what he expected, they have not been alarmed at ghosts ever since.

The wee Snarts’ method of ghost-gathering is explained by T.F. Thiselton-Dyer in his 1893 book The Ghost World, one of the finest books on ghostlore: “A favourite mode of capturing a ghost in days gone by was to entice it into something small, such as a bottle…” (p. 185). Maybe the Ghostbusters were overcomplicating things with their proton packs!

1820

In a work of family history titled The Huntingdon Peerage, Henry Nugent Bell relates an amusing anecdote about his efforts to track down family information at a church near Leicester. Late in the evening, Nugent Bell asked the parish clerk to guide him to the church’s cemetery so he could examine the epitaphs there. Aghast, the clerk said the cemetery was reputed to be haunted by the ghost of a warrior who “canters a marble horse of his over the gravestones at night.” The best the nervous clerk could do was to give Nugent Bell a lamp and some keys, “‘if as how I wished to go ghost-hunting alone.'” Indeed, on his own, Nugent Bell found the cemetery, and upon finishing his work there, he was horrified as “a warm living breath poured upon my cheek….” Turning around, “my eyes met the benevolent and inquisitive gaze, not of sheeted spectre, or life-assuming statue, but of bona-fide blood and bone, in their most honest and unalarming shape, an ass!” The clerk’s donkey had been lured inside the church by the light and the promise of shelter.

1825

According to the Star, a London newspaper, butcher John Benjamin delivered some meat. Afterward, he decided to wrap himself up with the leftover butcher paper (as you do). Apparently, he looked like a ghost, which did not sit well with the residents of the Hammersmith district.

As the good people of Hammersmith have long been ghost hunting, they seized the poor butcher, who was taken before the Magistrate….

See 1804 to better understand why those Hammersmith residents had little patience for folks dressed like ghosts.

🕷

London’s Weekly Dispatch printed a story — supposedly true and supposedly humorous — about a band of idle Ramsgate men who investigated a ghost rumored to haunt an outdoor spot. At the site, they saw “a white form” in the distance, but it didn’t answer their hails. They then shot at it (as you do). The tale continues:

A loud scream followed the [gun’s] report, and a female rushed forward wounded in the face and hand. Fortunately, our ghost-hunters had kept such a respectable distance that the lady was not much hurt, and the only evil consequence attending the affair was, that a worthy gentleman was interrupted in a little innocent armour, and part of the ghost-hunting crew retired from the town for a few days, till the lady, for good substantial reasons, agreed to forgive them.

1827

In Mary Ann Hedge’s novel The Fortunate Employ; Or, The Five Acres Ploughed, reports of ghostly activity at Westwood Grange become a touchy subject for Bentley, who says he’ll investigate the place.

‘I think we had better go ghost-hunting ourselves,’ said Eveleigh playfully, for he saw that was the only way to treat the subject in the present state of Bentley’s temper.

1828

In Caroline Bowles Southey’s travel book Chapters on Churchyards, first serialized in Blackwood’s, a friend of the author recounts an experience he had while on a fishing trip. As he wanders toward his inn, he’s met by waves of excited locals:

As the different groups scudded swiftly by me, I caught here and there a few disjointed words about ‘a ghost,’ and ‘the church yard,’ and ‘all in white,’ and ‘Old Andrew,’ and ‘ten-foot high,’ and ‘very awful!” Half tempted was I to turn with the stream, and wind up my day’s sport with a Ghost hunt, but [the pleasures of the inn] were irresistible attractions….

At the inn, the fisherman hears the backstory of the ghost, and he retells it to the reader. The series was reprinted in book form in 1829 and 1842 (with the G in “Ghost hunt” no longer capitalized).

1831

From a translation of Christian August Vulpius’s novel Rinaldo Rinaldini, Captain of Banditti:

Giorgio.— But as to the ghost-hunting expedition, I am your man. I will take my sabre.

Lisberta.— Of what use can it be? I will give you a church candle….

The original work is the 1797 German novel Rinaldo Rinaldini der Räuberhauptmann. Volume 1 and Volume 2 of an 1801 edition are available online, but I do not read German. I would love to learn what term it uses in this passage. Geisterjagd?

🕷

In the October 22 issue of The Mirror, Samuel Johnson is said to have

related with a grave face how old Mr. Cave of St. John’s Gate saw a ghost, and how this ghost was something of a shadowy being. He went himself on a ghost-hunt to Cock-lane, and was angry with John Wesley for not following up another scent of the same kind with proper spirit and perseverance.

1833

In a letter to the editor of The Bury and Norwich Post, J. Riches addresses the alleged haunting of the Syderstone Parsonage, where the Reverend John Stewart resided. Riches says that, upon “learning that several gentlemen had been sitting up in Mr. Stewart’s house all night,” he had expected that

other facts connected with that night’s ghost-hunting, as well as its previous and subsequent visitations, would have come out….

🕷

As the title suggests, Michael Banim’s novel The Ghost-Hunter and His Family has several uses of the term. Here are a couple of interesting ones:

Morris, persevering as he had been in his researches after fairies, ghosts, and other supernatural things, at last began to fear that his want of success was attributable … to a want of the faculty of perceiving them. But this growing conviction, though it sorely irked him, did not as yet induce the ghost-hunter to give up his wild and strange pursuit. (p. 40)

Barnaby and Jim both recognised him: it was our ghost-hunter — Morris Brady. (p. 96)

To be sure, Morris Brady should be recognized as one of the founding ghost hunters of fiction. The novel was reviewed by such leading journals as London’s The Athenæum and New Monthly Magazine, Dublin’s University Review, and New York’s The Knickerbocker. It was popular enough to be republished in 1852, 1863, and 1869.

1835

The Liverpool Mercury reported that a watchman came upon four men at 1:00 a.m. Finding them “under suspicious circumstances, and knowing several of them to be bad characters,” the watchmen brought them to the local police station. The men claimed they had gathered for no other purpose than to see a ghost that had been reported to haunt the park. What with

there being no specific charge against them, and ghost-hunting not being an offense at law, they were discharged.

🕷

London’s St. James’s Chronicle reported that, in Manchester, crowds were gathering nightly around an architect’s unoccupied office to hear “supernatural sounds,” including heavy footsteps, opening drawers, and rustling papers. The night watchmen found no sign of thieves, though they also heard the noises. Eventually, the sounds were discovered to be resonating from an attached pub. This didn’t stop the curious, though, and the report ends with this:

Yesterday, an over-valiant ghost-hunter was brought up at the New Bailey [Manchester’s courthouse], charged with willfully damaging one of the outer doors by kicking at it, in a vain attempt to frighten the ghost. He was reprimanded and discharged.

1837

From Richard Harris Barham’s short story “The Spectre of Tappington“:

‘Ghost time’s come!’ said Ingoldsby….

‘Hush!’ said Charles; ‘did I not hear a footstep?’

[The footsteps turn out to be caused by Mrs. Botherby “toddling to her chamber.”]

‘Good night, sir!’ said Mrs. Botherby.

‘Go to the d—l!’ said the disappointed ghost-hunter.

The next night (about two pages later), Ingoldsby tries again, hiding in a closet:

Here did the young ghost-hunter take up a position….

This tale became part of Barham’s book-length The Ingoldsby Legends, which remained popular enough to be published and republished in 1840, 1861, 1867, 1870, 1889, and 1894. Tom Ingoldsby, then, joins Morris Brady (see 1833) in being a key founding ghost hunter of fiction.