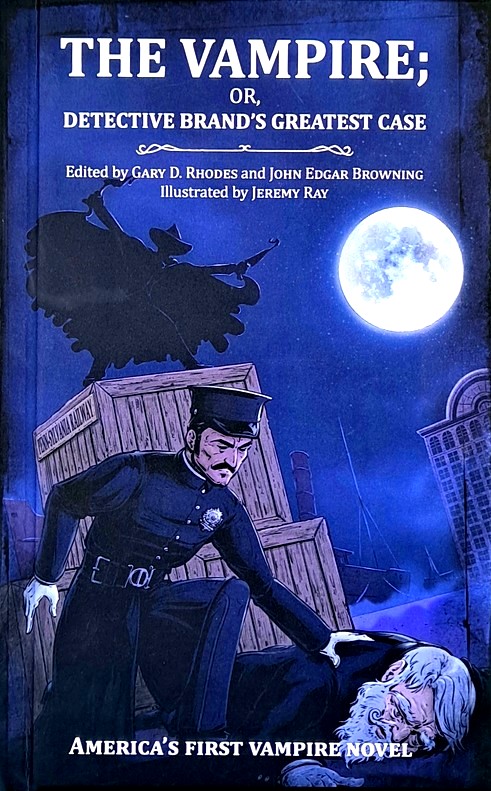

The title page of The Vampire; Or, Detective Brand’s Greatest Case (1885), as reprinted by Strangers from Nowhere Press, includes the name of an essay placed after the novel. That essay is Gary D. Rhodes and John Edgar Browning’s “America’s First Vampire Novel and the Supernatural as Artifice.” Those last four words were my first clue that the novel’s central detective, Carlton Brand, would turn out to be what I’ve come to call a debunking detective. In essence, debunking detective work involves meddling kids pulling the sheets off ghosts to reveal imposters underneath. Think of Sherlock Holmes in The Hound of the Baskervilles, Hercule Poirot in “The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb” or Miss Marple in “The Blue Geranium,” and even Thomas Carnacki in “The House Among the Laurels.”

Unlike the others, Carnacki usually digs down to the case’s root and finds an otherworldly pest there, and mystery stories with such verified supernatural elements have guided my selections for the Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives. The list is plenty long as it is, but it would be downright exhausting — and never exhaustive — if I were to include debunking detectives.

SPOILER: Yep, Brand discovers that the villain in The Vampire was employing “the Supernatural as Artifice.” Therefore, nope, he does not join the sleuths on my list. (I’ll revisit this decision if, in his second or third greatest case, Brand proves a werewolf is a human who, on special occasions, sprouts impressive body hair and proceeds to impolitely gnaw on other humans.) Given that the title culprit is more faux vampire than a certified supernatural one, this novel might be framed as America’s First Vampiresque Novel. And it’s really more detectivesque than vampiresque. Instead of coffins and castles and crucifixes, the focus is on investigations led by characters named Blakely and Brace and Brand.

This is certainly not a negative criticism. Rhodes and Browning explain in their essay that a solid tradition of non-supernatural horror literature existed in the U.S. during the 1800s. One strain, they say, involves “real-life horrors,” and the other stirs up a specter of the supernatural “only to rationalize it” (pp. 249-250). The second strain prepares the way for The Vampire as well as for Holmes and his debunking colleagues. Rhodes and Browning go on to describe Brand as being “prescient of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, who would not appear in print for another two years” (p. 255). In this regard, The Vampire might be viewed as much closer to Conan Doyle’s Holmes tale “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire” (1924) than to Bram Stoker’s vampire novel Dracula (1897).

If approached with this in mind, The Vampire becomes a fun, goofy, melodramatic, not-even-trying-to-be-realistic yarn one expects from a dime novel, which it originally was. In fact, I found it amusing to assess Brand’s performance in light of Sherlock-to-Come, a competition that I’m sad to say the American loses. Brand’s Plan A involves repeating Brace’s Plan A, which ended with that detective being murdered. Brand’s Plan B is to repeat Plan A, which ends with his being outmaneuvered by a character known as Miss Marita Madriea, a mysterious figure with a whiff of Irene-Adler-to-Come. Brand’s Plan C? Repeat Plan A. Ask Goldilocks: the third time’s a charm.

Meanwhile, poor Helena Porras is having a miserable first visit to the States, what with being drugged, abducted, nearly drowned, held for ransom, drugged, and abducted. I was glad to see that, though she’s stuck in the damsel-in-distress role, Porras still exhibits a glimmer of self-preservation agency.

My advice to interested readers, then, is to go in expecting a detective adventure. Expecting a vampire novel might lead to some disappointment.

[This paragraph is bracketed because it refers to the Advance Reader Copy I was kindly sent, one with a sticker saying the “product may not be final.” There are a fair number of errors in the text I read. The first page of the novel proper, for instance, mentions “A serious of mysterious deaths” when that should clearly read a series of mysterious deaths. I asked the publisher about the errors and was informed that leaving in the original flubs was intentional, allowing today’s readers to experience the work as readers did in 1885. That’s a bold editorial choice, especially since it goes unannounced. Thus, a character named Anchona is referred to as “Anehona” at one point, and another named Somerton as “Sornerton.” Minor stuff — barely a blip in reading comprehension. It’s a bit tougher to figure what goes unspoken when our bad guy steps up to a boat “and placing oars in its motioned Brand to embark.” A reader might raise an eyebrow when Brand is about to handcuff Madriea and she “extends her writits” — indeed, extending her wrists would seem more comfortable — or when that bad guy boasts “you will not tang me” rather than voice his views on being hanged. I’ll also toss in the several commas that appear as periods and the multiple times “he” shows up as “be.” I haven’t seen the original novel, but I’ve worked with enough old texts to suspect these last errors stem from the scanning/OCR process, and I hope they’re double-checked for the books available for purchase. Typos are gnats flying around readers’ eyes, and the fewer the better.]

Regardless of those tiny bugs, The Vampire is a fun glimpse at the cheap entertainment of an earlier generation. Personally, I don’t think the work adds much to the history of vampire literature. Call me a purist, but — much as I like my occult detectives to face the actual supernatural — I prefer my vampires to emerge at dusk, slake their unholy thirst for human blood (either politely or impolitely), maybe burst into flame in sunlight — and would it kill ya to climb down a castle wall like a lizard now and again? However, the novel is a noteworthy addition to the debunking detective tradition.

By the way, feel free to snoop around the Chronological Bibliography of Early Occult Detectives, if you have a few moments.

— Tim

Dang. I was hoping this was a treasure. Not that I won’t read it anyway. Pulp detectives are good enough for me.

LikeLiked by 2 people