Another “First Celebrity Ghost Hunter”

In a sense, Ada Goodrich-Freer (1857-1931) was a model for at least two ghost hunters who followed: Elliott O’Donnell and Harry Price, both of whom compete for the title of “the first celebritiy ghost hunter.” All three were accused of embellishing — if not outright falsifying — their findings to bolster their reputations and the popularity of their ghost-hunting chronicles. And if Borley Rectory was where Harry Price “met his Waterloo,” then Goodrich-Freer’s met hers at Ballechin House.

But let’s start with a slightly earlier ghost hunt, namely, Goodrich-Freer’s investigation of Clandon Park, an 18th-century mansion in Surrey, England. In January, 1896, she — using her usual mysterious pen name “X” — told readers of Borderland that the story about a ghost at Clandon Park had been twisted and distorted. She summarizes two different accounts of a tenant at the mansion encountering a phantom woman wearing a cream-colored dress. In one version, the tenant is a French financier — in the other, it’s a widow. In one, the ghost is armed with a knife — in the other, she isn’t. Goodrich-Freer ends this preliminary report by saying:

The present writer has had the advantage of being allowed to make some inquiries on the spot on behalf of the Society for Psychical Research, but the amount of evidence so far obtained has not yet justified a formal report to the Society, and any expression of opinion on the matter might, in the meanwhile, be justly regarded as premature.

A Follow-Up Report on Clandon Park

Over a year later, Goodrich-Freer’s follow-up report was published in the same journal. She explains the delay: “[A]s a matter of courtesy to the owner of the house, publication was deferred till permission had been received to make known the real circumstances; with, or, if desired, without, the names of persons concerned, or even of the place itself.” Here, we learn that her investigation was suggested by the Vice-President of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute. He’s a figure who would return in the Ballechin House investigation.

Goodrich-Freer provides some background on the Clandon Park haunting before narrating her experience there. After tea with the residents, the ghost hunter held a disappointing (and presumably brief) vigil in “four rooms alleged to haunted.” She then prepared for dinner, her hostess having guided her to a bedroom to dress. But she wished to ask something of the hostess and, so, stepped into the hall. Instead of finding the hostess, though, Goodrich-Freer claims to have seen the ghost:

She was cloaked and hooded, her dress of yellowish white satin gleamed where her cloak parted. . . . Just as we met — when I could have touched her — she vanished. I discovered later that my description of her corresponds with that of other seers who have met the same figure before and since.

Now, I’m not one to demand that a specter wait until midnight to appear to a ghost hunter. All I’m saying is that this specter was suspiciously accommodating to Goodrich-Freer. That’s all I’m saying.

Trouble at Ballechin House

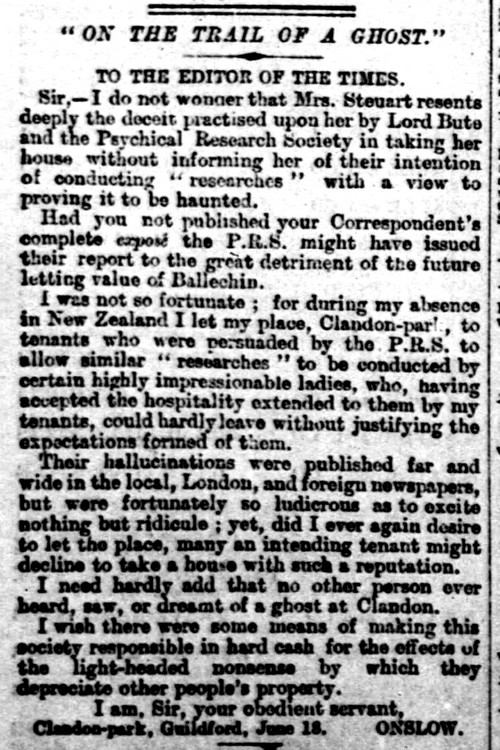

Later in 1897, up in Scotland, Ballechin House was garnering attention as being another mansion where ghostly manifestations were — not limited to — but focused in four rooms. This is according to an article titled “On the Trail of a Ghost,” printed in London’s The Times (and reprinted in Borderland along with the replies mentioned below), which also reported that Crichton-Stuart had rented the house for three months so that the some of his SPR colleagues could investigate it. Though Goodrich-Freer is not identified by name, the correspondent — who also remains anonymous* — explains that she was there to serve as hostess while a number of interested investigators came and went.

The correspondent was one of those visitors. And the upshot of his report is that there was nothing to substantiate the claim that Ballechin House was supernaturally haunted. The noises he heard could be attributed to wind and to pipes and to the fact that “ordinary noises can be transmitted in that house with unusual facility and to unusual distances.” One woman’s account of “the ghost of half a woman sitting on her fellow servant’s bed,” he says, should be taken with “a grain or two of salt.”

When this report was published, it created quite a stir. Goodrich-Freer wrote to The Times to express her objection to the correspondent’s revealing the specific house being investigated. After all, ghost-hunter decorum dictates that one respect the privacy of the haunted party. She also pointed out that the correspondent drew his conclusions after having spent only 48 hours at Ballechin House. Harold Saunders, the butler there, also wrote, explaining how his scoffing when hearing about the ghostly encounters from others halted when he also began to experience weird noises and other spectral sensations. The original article, the letters from Goodrich-Freer and Saunders, and related pieces published in The Times can be read in full at “A Return to Ballechin House (with New Old Research Sources Related Thereto),” which is also linked at the end of this post.

The SPR Distanced Itself

Meanwhile, Frederic Myers and Henry Sidgwick, officers of the SPR, wrote to distance the Society from any and all affiliation with the investigation. Even the owner of Clandon Park wrote to The Times to complain about how the SPR and, by association, Goodrich-Freer had shown no reservations in naming that residence in earlier articles.

All and all, this was more bad press than the SPR cared to tolerate. Goodrich-Freer found her contributions there no longer appreciated and her membership ended. No doubt, this blow damaged her reputation as a ghost hunter and probably contributed both to her abandonment of that pursuit as well as to the dubious reputation that would come to, ahem, haunt her.

A Ghost Hunter’s Afterlife

Nonetheless, she and Crichton-Stuart turned revenant into revenue, if I may coin a phrase. They penned one of the few book-length chronicles of a ghost hunt: The Alleged Haunting of B– House, published in 1899, a couple of years after all the hubbub. (Goodrich-Freer had previously written a briefer chronicle of the ghost hunt for Part II of an article in The Twentieth Century.) Furthermore, Goodrich-Freer’s chronicle of investigating Hampton Court Palace is included in The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook. It’s a chronicle that reveals that — if her claims about encountering ghosts were questionable — she had many answers about late-Victorian theories explaining such encounters.

*Some online sources — such as this one, this one, and this one — name the correspondent as J. Callender Ross. However, I haven’t found any source from the 1890s or early 1900s confirming this. I would be very glad to learn how the exposé writer was identified as Ross.